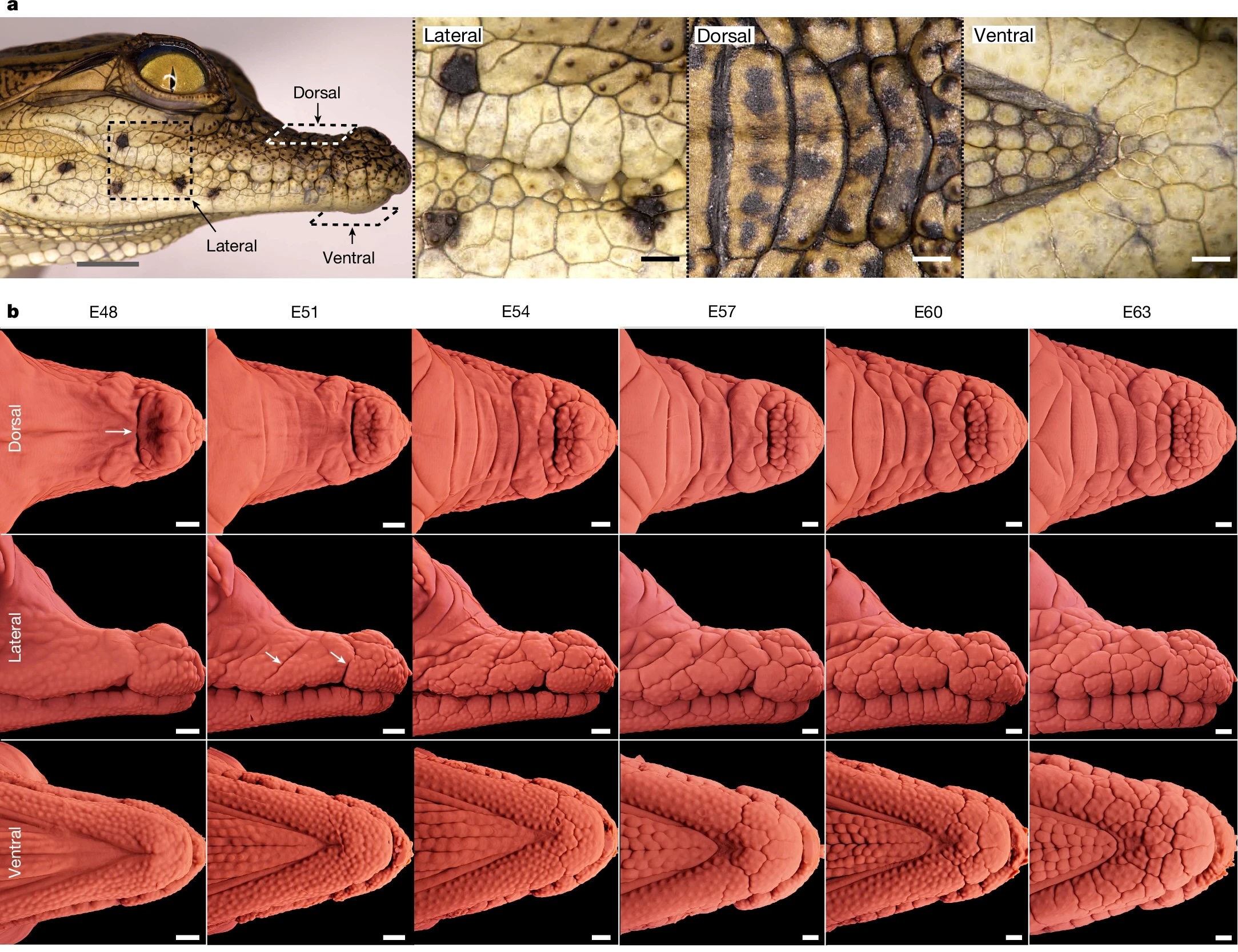

How did the crocodile get its smile? The functions that give the reptile its signature wrinkled snout aren’t quite the same as those responsible for the rest of its scales, with precise mechanical processes folding the scaly leer into shape long before hatching.

Getting a detailed picture of what’s going on inside a crocodile egg is no easy feat, but researchers from the Laboratory of Artificial and Natural Evolution (LANE) at the University of Geneva in Switzerland have cracked it.

Previously, biological scientist Michel Milinkovitch, lab leader at the LANE, found that the irregular polygonal head scales of crocodiles are formed quite differently from structures that give rise to arrangements of mammal’s hairs, bird’s feathers, and reptile’s scales.

These features originate from thickened sections of the embryo’s outermost skin layer, called placodes, and their arrangement is determined by waves of interacting chemistry known as Turing patterns, which are encoded in the animals’ genes.

“The patterning of irregular crocodile head scales provides a fascinating exception to this paradigm,” the team explains in a video presenting the study’s findings.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

Crocodile’s head scales are instead sculpted by a mechanical process, which the team originally attributed to tensile stress, meaning the furrows between scales would be similar to the stretch marks we humans might experience during a growth spurt.

While they may have been right about the mechanical source of scale patterning, the team has ditched the tensile stress theory after the new study revealed an entirely different force is at work.

“Here we show that the patterning of crocodile head scales in fact emerges from compressive mechanical instabilities,” the authors write.

At first, the embryonic crocodile begins with a smooth jaw, which is gradually creased as the skin grows. These premature wrinkles connect to form irregular scales, large and elongated on the upper jaw, while the lower jaw is populated with smaller polygons.

They figured this out by injecting Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) eggs with epidermal growth factor (EGF), a protein that increases the epidermis’s stiffness and the speed of its growth, resulting in embryos with head scales wrought by a much exaggerated version of the usual process.

“This ‘brainy’ network of skin folds partially relaxes towards a pattern of smaller polygonal head scales in hatched crocodiles,” the authors write, “that is, highly similar to the head-scale patterns of caimans.”

The skin folding on EGF-treated crocodiles that were allowed to hatch four weeks after treatment was “labyrinthine”, with smaller polygonal head scales.

These experiments, along with computer simulations that further confirmed the laboratory findings, revealed normal Nile crocodile head-scale patterning is the result of the skin growing faster than the bone beneath it, as well as the mismatched stiffness (but not growth rate) of the epidermis and the dermis.

It’s quite the opposite of a teenager’s growth spurt problems: the crocodile’s skin grows faster than the rest of its body can ‘fill’, resulting in folds more akin to those of a shar pei puppy than the stretch marks on a lanky human.

It also suggests the different head-scale patterns of various crocodilians may be due to variations in embryonic skin growth favored by evolution.

The research was published in Nature.

Leave a Comment