A young male humpback whale has been spotted fraternizing with females in two different groups located on opposite sides of the world, with a record-breaking journey of more than 13,000 kilometers (or 8000 miles) between them.

The sightings have baffled the marine biologists, oceanographers, and cetacean experts who analyzed the sightings. Despite the occasional overlap, humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) generally stick to their distinct breeding stocks, of which there are seven in the Southern Hemisphere.

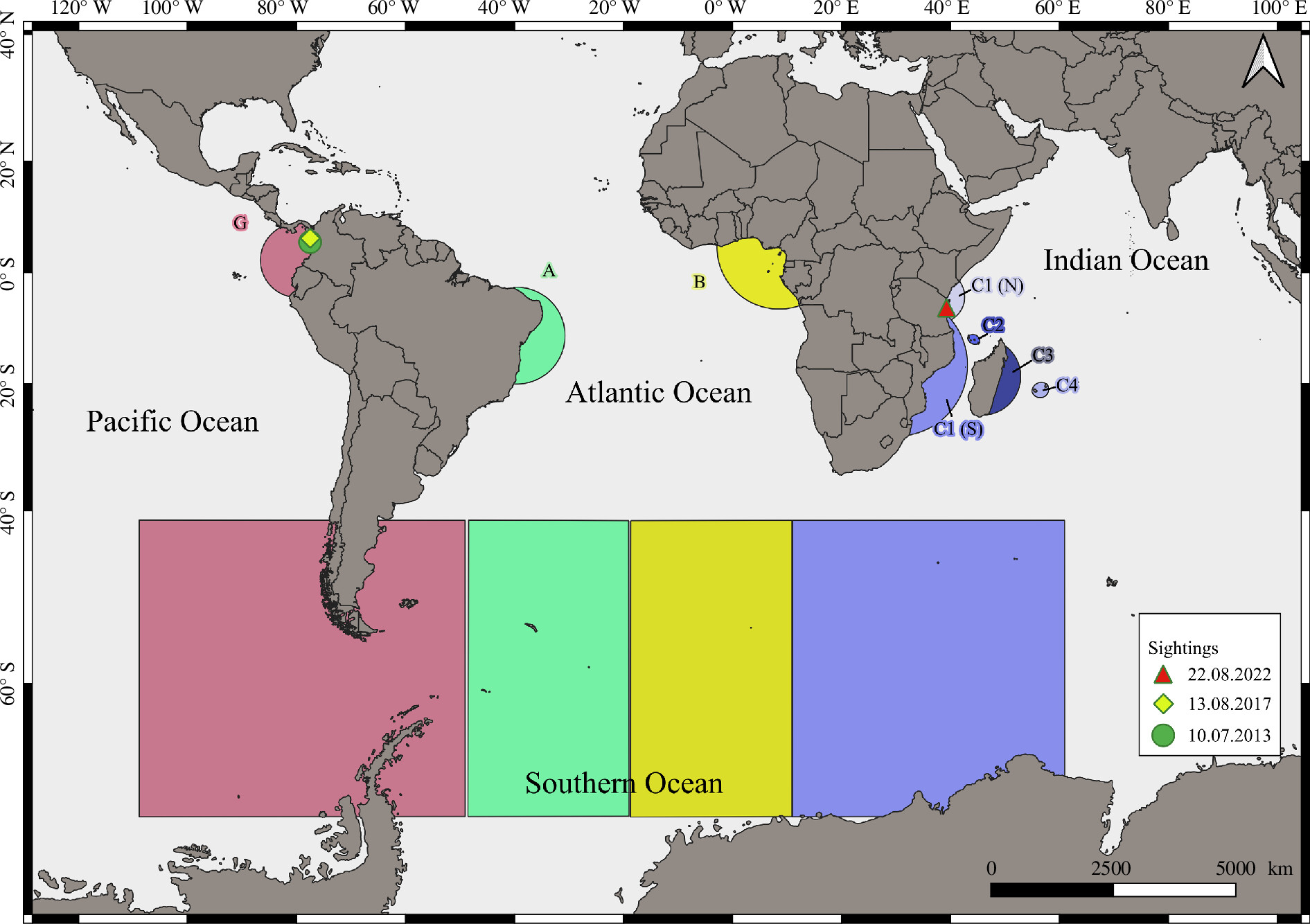

The male was spotted with other humpbacks in photos posted to the whale sighting platform Happywhale, first in the Pacific Ocean near Columbia in 2013, in the Gulf of Tribugá just above the equator, and then, nine years later, hanging out with an entirely different group off the coast of Fumba, a Tanzanian village in Zanzibar, in the southwest Indian Ocean.

That’s a minimum distance of 13,046 kilometers between sightings of the same whale, and the first record of a humpback whale alternating between Pacific and Indian Ocean wintering grounds.

Such a record-breaking range raises the question: Who is this veritable playboy of the whale world? And why does he cast his social web so far?

For whales, breeding and feeding can take place in substantially separate locations, so migrations of up to 8,000 kilometers in a single direction north or south aren’t unheard of. But longitudinal migrations – as in this instance – are quite unusual.

The whale might have been driven by increased competition with other males for breeding and food, as humpback numbers globally recover from the havoc wrought on them historically.

His journey could also be a response to changes in his environment and climate that are impacting krill distribution in the Southern Ocean, a vital food source for the humpbacks.

“It cannot be precisely determined when the breeding area shift happened for this whale, but it can be said that the individual appears to have been a sexually mature male when first sighted in 2013 and during the movement between the east Pacific and western Indian Ocean after August 2017,” the authors write.

“When this male was seen in Zanzibar in 2022, assuming sexual maturity at a minimum of 6 years of age, he was at least 15 years old.”

We don’t know for sure, but given his age and the fact both pictures showed him keeping the company of females, the researchers think it’s likely his epic journey was made in the name of procreation, especially since the sightings were recorded around breeding season.

It’s impossible to know the exact route he took based on the photos alone, but despite the impressive mileage, it was probably an easy hitchhike on the prevailing currents that run down the western coast of South America, around the Cape Horn, across the Atlantic Ocean and around the Cape of Good Hope before arriving in the Indian Ocean.

“[It] underlines the importance of transboundary research effort and citizen science to understand potential drivers and population impact of interoceanic movements of humpback whales,” the authors conclude.

With better tracking, we may get a better idea of what drives a whale from shore to distant shore, and whether this intrepid traveller is a migrant starved out of his territory, or simply a young man with a lust for the open road.

The research was published in Royal Society Open Science.

Leave a Comment