“dFAD.” Sounds like it could be the name of a hot new DJ on the club scene somewhere large and urban and teeming with people. Of course, in this context, it’s not; though if anyone needs a new DJ name, I think “dFAD” is probably still up for grabs.

The dFAD in question here is an acronym for something called a drifting Fish Aggregation Device (dFAD) used by tuna purse seine fishing fleets to attract and aggregate commercially valuable schooling fish. But there are also times when dFADs drift into protected waters where the fleets don’t have legal fishing access, which is one of the places in this story where TNC comes in.

TNC’s FAD Watch Program: Interception Before Impact

Such off-limits areas include Kingman Reef and TNC’s Palmyra Atoll within the U.S.’s Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument (PRIMNM) in the Central Pacific (about 1000 miles south of Hawai’i and 6 degrees above the equator). Palmyra Atoll and Kingman Reef are themselves part of National Wildlife Refuges within the Marine National Monument.

All told, the refuges and the monument, protect approximately 13 million acres of ocean and coral reef surrounding 580 acres of emergent land, including TNC’s 250-acre Palmyra Atoll Preserve. This is the largest swath of ocean and islands protected under a single jurisdiction in the world.

“We began documenting dFAD groundings on Palmyra in 2008,” says Kydd Pollock, TNC’s pelagic conversation strategy lead. “Over the next decade, we noticed increasing numbers of these devices grounding on our tropical reefs. Meer minutes of a dFAD’s long tail dragging across sensitive corals causes damage that can take years to heal. Fortunately, dFADs come with built-in location technology that is the foundation of the FAD Watch Program. Palmyra FAD Watch was the first program of its kind in the Pacific Ocean.”

Each individual dFAD is a mash up of a few key, well, ingredients: a floating raft or buoyant structure, a satellite tracking buoy with an echo sounder, and a long tail—often hundreds of feet long—dangling beneath the surface. The rafts are often constructed of bamboo, floats, synthetic netting, PVC pipes and the tails are made of wrapped netting, ropes, shade cloth, tarps and organic material like palm fronds. They all tend to look different, but also the same.

Like a remix. Everyone puts their own spin on the assembly depending on the resources available to them at the time. Approximately 45,000 to 65,000 dFADs are deployed across the Pacific Ocean every year. They are tracked via satellite, but given the sheer number of devices and oceanic currents, the fate of 80% of dFADs is unknown. Because they are relatively low cost to assemble, such losses amount to far less than the value they create for the fishing fleets.

How FAD Watch Works

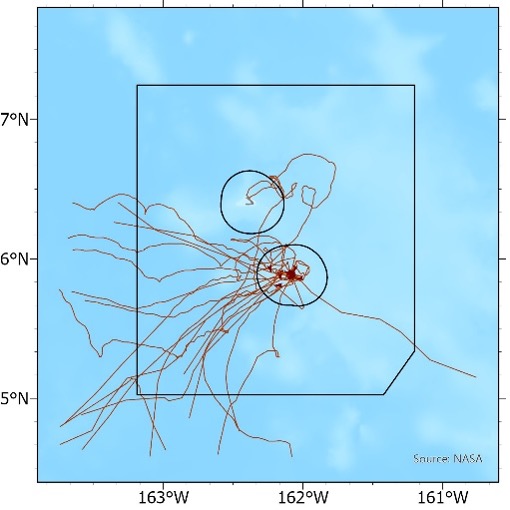

Through a structured and very collaborative agreement, American and Spanish purse seine fishing fleets provide TNC with near-real-time dFAD location data so researchers can track the devices as they drift through the protected ocean habitat around Palmyra Atoll and Kingman Reef.

The data is collated to monitor dFAD locations and help guide dFAD recovery when any drift within 6 nautical miles of Palmyra. If dFADs are on a grounding course with Palmyra’s reef, TNC can deploy a vessel with a team from the atoll-based research facility to intercept the dFAD before the sensitive coral reef is impacted.

The fishing companies also provide TNC access to oceanographic and fish biomass data from the satellite buoys tethered to dFADs. TNC and partners are able to better understand the relationship between Bluewater Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), like PRIMNM, as well as smaller scale oceanic processes in the central Pacific, highly migratory fish movements through an MPA, and the environmental impacts associated with commercial purse seine tuna fishing equipment.

Catching and Recovering a dFAD is Not Nearly as Easy as it Sounds

“Retrieving a dFAD is always a pretty big undertaking,” says Pollock. “And an urgent one, because if we miss it—and they are not always easy to spot on the open ocean—it could ground before we find it. Then once we find it—and the Palmyra research station only has one boat big enough for recovery efforts—we have to haul the whole dFAD, including that crazy long tail aboard the boat.. And it’s all done by four people (on average) doing everything by hand. Right now, we don’t have a boat with a crane or any other kind of mechanical assistance. It’s all brute strength and determination—definitely a work out.”

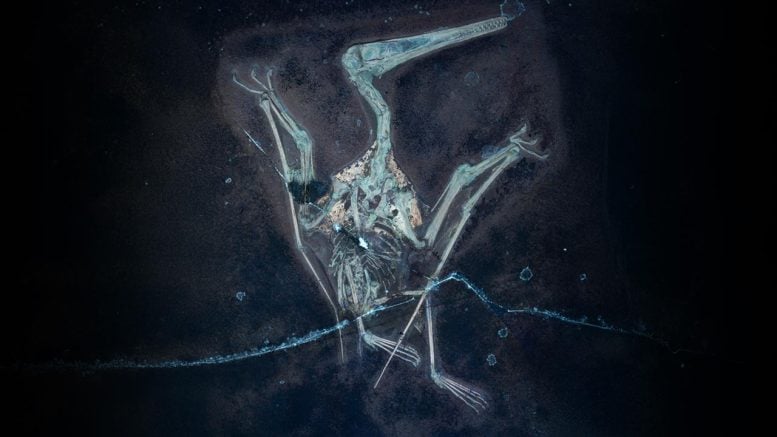

Recovering a dFAD from the waters around Palmyra can be an arduous, labor-intensive process. The images below show the essential steps that are part of every dFAD recovery.

to remove the tail of a dFAD that snagged on the reef. © Daniel Clifford/TNC

Beyond Palmyra: the Future of FAD Watch

Since 2021, FAD Watch has doubled the dFAD tracking geofence area and fishery data collection, more than doubled the number of vessels included in the FAD Watch program, and avoided more than 50 dFAD grounding events because TNC intercepted the devices outside Palmyra’s fragile reefs. Additionally, more than 5000 feet of coral-destroying ropes and netting have been removed from the ocean before they could impact Palmyra’s reef ecosystem or entangle marine life.

TNC is also developing and testing strategies for repurposing the recovered satellite buoys for research and for supporting conservation-oriented artisanal fishing communities in places like Micronesia.

This successful work is made possible by a solid partnership between TNC and the commercial tuna purse seine fishing industry. Now the program is focusing efforts on dFAD management and conservation protocols with the goal of expanding FAD Watch to other Pacific Island nations.

As of 2024, there are 22 fishing companies and more than 35 vessels participating in the program. Discussions to add additional companies and vessels are currently ongoing. Increasing the number of collaborating vessels is critical to TNC being able to improve and strengthen this conservation initiative.

“Through FAD Watch,” notes Pollock, “TNC scientists not only help protect Palmyra’s reefs, they are also able to use the data to compile unique information on the interaction of dFADs, pelagic fish biomass and Bluewater MPAs. This important data provides crucial insights for improving the science of managing Bluewater MPAs at Palmyra and beyond.”

Leave a Comment