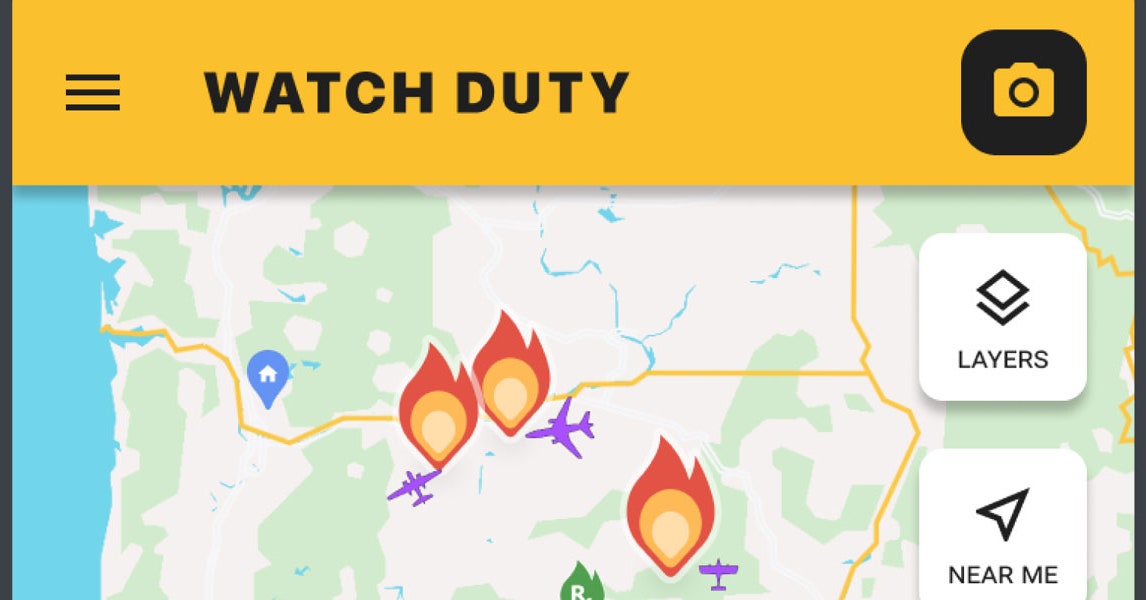

The ongoing wildfires in L.A. are among the most destructive and terrifying disasters to ever hit the city. As of the time of publication, five people have died, 27,000 acres have burned and at least 130,000 people are under evacuation orders. And the scope of the tragedy is just coming into focus.

We asked Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness and an associate professor of professional practice in climate at the Columbia Climate School, about the connection to climate change, why these fires have been so devastating and what can be done about wildfires going forward.

Why have the L.A. fires spread so fast and so ferociously?

There are a few factors at play here, but one of the biggest is that you have prolonged dry spells and low humidity, the things that drive wildfire danger to begin with. It tends to be more pronounced this time of year in California, especially when there’s been very little rainfall. And then you have the Santa Ana winds coming from the desert—very, very high winds, as much as 100 miles per hour. Once you get a spark, those things just blow.

There are some unique features in the LA fires as well. You have very densely populated areas and forested areas and very hilly areas. As heat rises with the winds, you have the very dry fuel that burns on an upward slope and moves quickly up the hillsides.

Is climate change playing a role here?

In general, wildfires are something where we do see a clearer signal for the impacts of climate change. It’s pretty well established that we’re seeing increases in the frequency of wildfires, and that’s driven by an increase in droughts and a lot of other factors. There have been numerous studies in Europe, in the US and elsewhere that show there’s that influence [from climate change], and we would expect that influence to grow.

Why are these areas of L.A. that are burning so vulnerable to wildfire?

Back in the day when these homes were being built, they were little bungalows that were developed and maybe bought on the cheap by actors working in Hollywood in the 20th century. And now they’re sought after properties. They are very expensive. Everybody wants to live there, but the infrastructure was never built for that many people.

Also, narrow and hilly roads make access to these areas very difficult. After the Getty fire a couple years ago, I had the opportunity to tour some of the affected areas with members of the LA Fire Department. We’re driving up these narrow roads into the hills of the areas that were burned, and we were in an SUV. They were saying, “Imagine trying to get equipment up here—we’re having enough trouble navigating in an SUV on a normal day.” Now you have people evacuating. You’ve got a fire truck, and you have trouble making the the turns on these roads.

The other factor is that one of the more effective ways to prevent fires is to manage the foliage on your property. But you have people who are paying millions of dollars for these homes, and they want to have shade on the porch.

Due to the tremendous and unprecedented demand for water, fire hydrants were running dry. Can you comment on this?

L.A. itself was built in an area that has always had chronic pressure on natural resources, water being chief among them. That’s only being made worse by climate change. But we also have more and more people living there. And so I think any solutions to reducing the risk [of wildfire] will have to include water as part of that conversation. A combination of things needs to be looked at, not only in terms of the longer-term development of the area, but also in terms of reducing the risk and the impact of these kinds of disasters. More robust policies are going to be needed that value investment in water infrastructure with greater consideration towards things like wildfires and underlying vulnerability.

What do you think will be the lasting impacts of these fires?

We’re seeing all these reports about celebrities who have lost their homes. While I would never belittle anybody’s loss, there are a lot of people who have lost homes who are going to be fine. They’re going to recover, they’re going to have insurance, they’re going to have access to savings, they’re going to buy new stuff. And then there are a lot of people who have lost everything and who are not going to be able to recover, who are going to go into debt, who are going to have residual stressors that can lead to health and mental health issues. A lot of people were barely scraping by, and this will push more people over the edge. Even accessing some disaster assistance programs can take years and can be very complicated and very difficult to do if you don’t have a lawyer or an accountant to help you through it. For most people, the recovery doesn’t take weeks or months. It can take years and sometimes even decades for communities to recover.

As we’re seeing more and more disaster events, it raises questions [about risk] and if insurers are going to keep insuring homes in the long run. Increasingly, it seems the answer is no.

Will people rebuild in these same areas?

Absolutely. Whether or not they should is another question. Our disaster policy in general is focused on rebuilding. It’s pivoted from how it used to be—rebuilding the way it was. It’s changed a bit into rebuild more resilient. It will be interesting to see if they take the time to rezone things or change building codes. The Hollywood Hills and the Palisades are areas where people want to live, and if these people don’t rebuild, someone else will be there to rebuild in their place.

As we’re seeing more and more disaster events, it raises questions [about risk] and if insurers are going to keep insuring homes in the long run. Increasingly, it seems the answer is no. Are banks going to keep giving out mortgages for houses that might be destroyed by a natural disaster if they can’t be insured? Going forward, these questions will pose larger existential crises for the real estate market.

What can people who live in areas that are vulnerable to fires do to protect themselves?

There’s actually a lot you can do to mitigate or reduce your vulnerability. One of them is just the management of trees and vegetation on your property—cutting back tree limbs and creating more distance between your house and the forested areas. Choosing the right types of plants to grow, like ones that are more fire or drought resistant, can have a big impact. Also building with fire resistant materials can go a long way.

Residents also need to be engaged and involved. The reasons why the fire department doesn’t have all the resources it needs are a function of the tax dollars at work. That’s where civic engagement is really important. If roads aren’t being expanded to allow fire trucks up and down more easily, we need people at those meetings saying, “Yes, we do need that.” This is where local politics matter far more than national politics in terms of involvement, because when you are in danger, that’s where the resources are deployed that are either going to get there in time or not.

It’s also a good opportunity for residents, whether they’re affected or not, to review their insurance policies, and examine what’s covered and what’s not. A lot of times, people think things are covered when ultimately they’re not.

And even if they are not in an evacuation zone, people should consider, if you had to leave very quickly, where would you go? What would you need to take with you? In any disaster situation, you’re either going to have to stay in one place for a long time, or you’re going to have to leave very quickly. What is it that you need to be healthy, comfortable and stay connected?

The bottom line here is that L.A.’s table is set for disasters due to a lot of policies that don’t necessarily have anything to do with disaster management, but have to do with transportation policy, housing policy, natural resources policy, economic development policy, each with their own incentives on how to develop these and their own priorities and their own interest groups. At the end of the day, we’re left with areas with a high exposure to hazards and limited resources to respond to them because of decisions that have been made based on all these other ways of thinking. The thinking needs to become more integrated and disaster resilience also needs to be more fully integrated in the process.

What resources are available to people affected by these fires?

The best places to go are always the local emergency management. They’re going to have the latest and best access to resources. Because this is still an active burning area, local fire department and local emergency services, in terms of your risk and the safety of coming and going, are the best resources. And of course, the Red Cross has the latest information as well as access to shelters and other resources. There will also be more resources coming through other organizations as disaster declarations are made through FEMA and other agencies.

Leave a Comment