The good news has been out for some time now: the latest round of Periodic Labour Force Survey (July 2023 to June 2024) shows a continuation of the trend of increased labour force participation rate (LFPR) of women. As we celebrate, a nuanced look at the multitude of women in rural areas who form the bulk of this trend is in order.

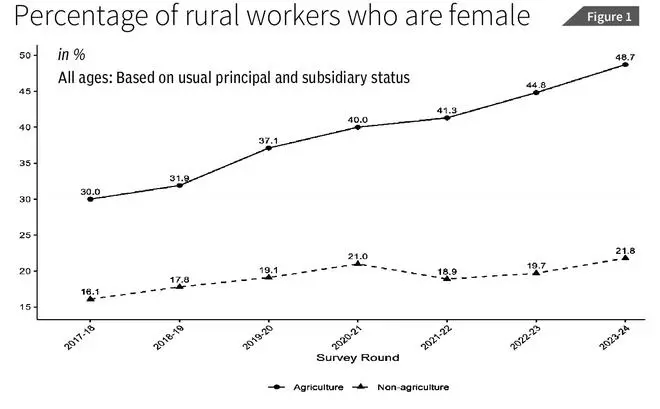

First, LFPR for rural women has nearly doubled from 18.2 per cent to 35.5 per cent in the last six years (2017-18 to 2023-24), while the change for their urban counterparts was subdued (from 15.9 per cent to 22.3 per cent for the same period). Second, taking a granular look at the rural women participation, the share in agriculture has increased more compared to the share in non-agricultural activities (Figure 1)

The increased labour force participation of rural women in agriculture has brought in a discussion around the reduced burden of drudgery due to various government schemes like Ujjwala and Har Ghar Jal. Reduced drudgery has provided greater scope for rural women and as a first step, they are working more on what is closest to them: the farms. While accepting the role of reduced drudgery and underlying welfare measures, we need to examine age-group specific nuances to get a better understanding of the contours of increased LFPR.

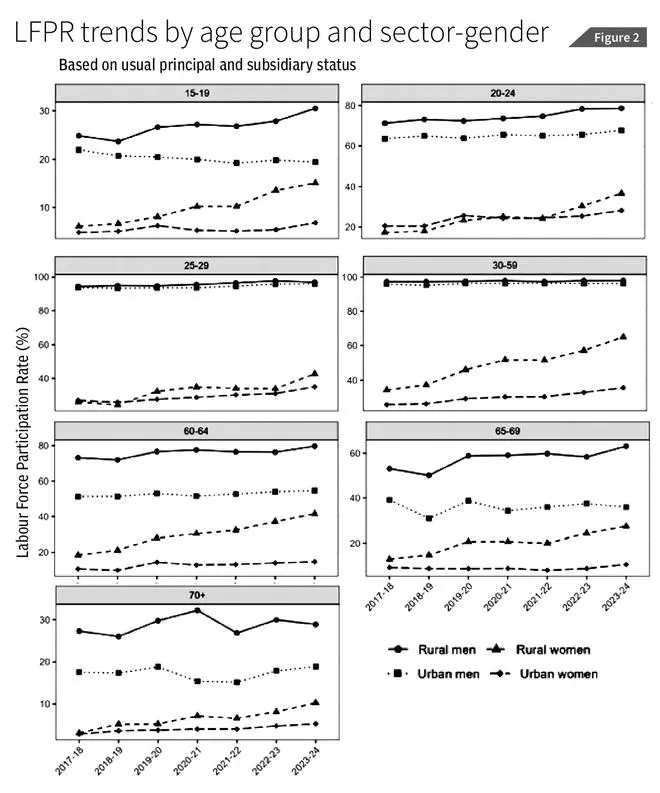

The age-specific patterns from the PLFS data helps to highlight some interesting facets of LFPR. In Figure 2, we show the LFPR for rural and urban labour force across age groups.

First, there is a sharper increase in LFPR for rural women in the age group 15-19 compared to urban women and men (Figure 2, sub-panel 1): LFPR has nearly tripled from 5 per cent to 15 per cent (2017-18 to 2023-24). For rural men, the rise has been from 25 per cent to 30 per cent over the same period. For urban women, the rise has been muted while for urban men, labour force participation has declined during the same time.

The standout trend observed for rural teens is surprising. Anticipating future gains to be made with participation in the workforce, individuals in this age group should invest in obtaining human capital, made easier by the fact that their parents are now productively participating in the workforce. While there will certainly be households where young members need to earn their livelihood, the broad trend should be steady or falling labour force participation for this age bracket.

Senior women

Secondly, on the other spectrum of the age, LFPR for rural women of age 60 and above is increasing (sub-panel 5,6,7). Similar to the case of the 15-19 age group, increasing labour force participation of these senior women is unparalleled. It is also observed for rural men, but much less pronounced.

This in fact brings us to a characteristic observation: senior citizens’ participation in the labour force being consistently higher for rural areas than urban. Expectedly, for the age group 25-59, all men are in the labour force. However, as we cross the colloquial retirement age, 80 per cent of the rural men continue to be in the labour force while the percentage drops to 50 per cent for urban men. The trend continues as we traverse further on the age spectrum.

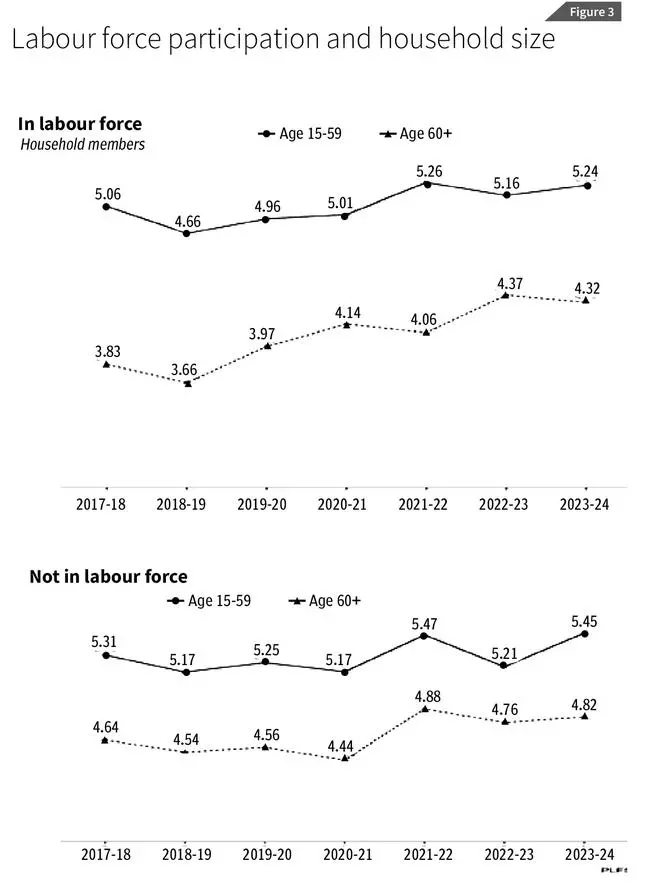

The phenomenon of senior citizens, especially women, at work can be concerning. It is difficult to align this development to an expression of agency of rural elderly women. A more plausible reasoning is that elderly women will choose to be in the workforce for certain specific household attributes.

For example, smaller households seem to be associated closely with women in the labour force, underlining the possibility of lack of earning members driving these women to labour force participation. Figure 3 shows that for elderly women in the workforce, the household size is smaller compared to non-working elderly women.

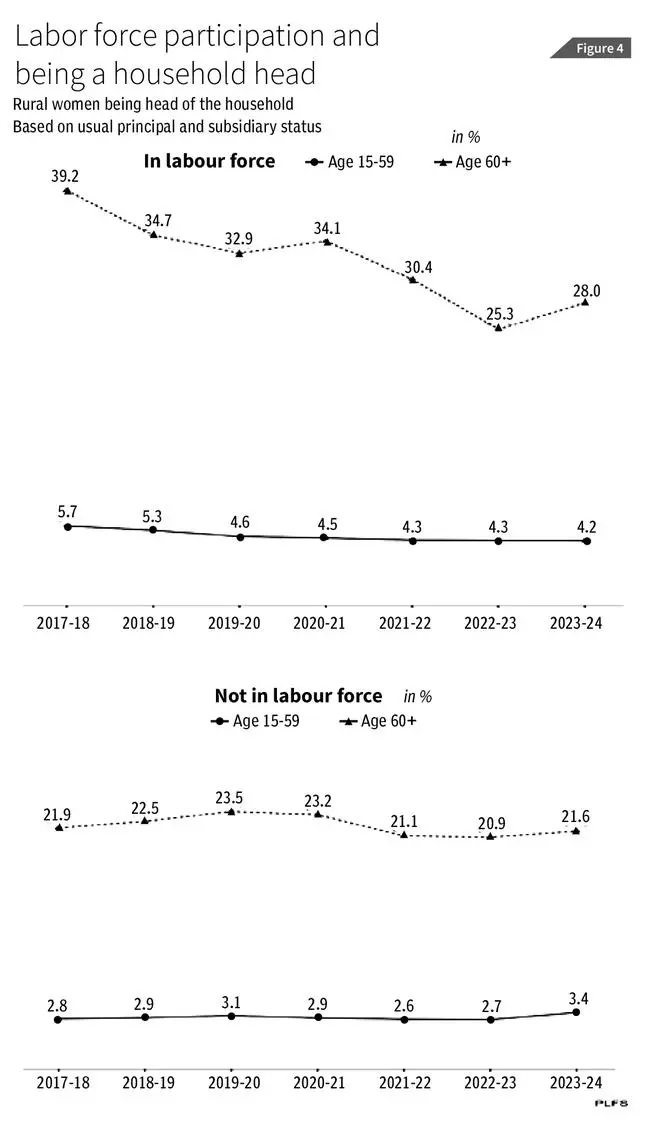

Household heads

Again, female-headed households can either be ceremonial, coming from the virtue of being the eldest person in the household, or reflect the absence of a male ‘partner’. Figure 4 shows that elderly women, in general, are more likely to be household heads which is expected. However, rural elderly women in the workforce are even more likely to be the household heads than their not-in-the-workforce counterparts.

Thus, their labour force participation might be driven by economic necessity along with the headship that comes with age. The fact that these workforce-household characteristic relationships are much less pronounced for rural women aged 15-59 further strengthens this argument. This indicates that labour force participation of older rural women might be reflecting their vulnerable economic position rather than positive workforce engagement. A broader point is the need to enhance the support structure for rural elderly, to address their labour force participation arising out of absence of support structure.

The growing rural women workforce participation undoubtedly marks the path towards exercise of full agency. Part of this positive development is attributed to reduced drudgery of household work made possible by government schemes. But when we examine the two ends of the age spectrum of rural women, we see some signs that this development could be arising more out of necessity than expression of agency. The standout rise in workforce participation of rural teenage girls and elderly people warrants a deeper analysis.

Thus, it is difficult to conclude that the rural participation seen for women is a positive herald, before understanding the following: What has made them participate more in agriculture in the last few years? Are they substituting men in agriculture, who are increasingly seeking non-agricultural employment or moving out of the rural belt? Is increased participation being driven by compulsion of other earning members leaving for non-agricultural work? Or is participation in agriculture a constrained choice: arising out of greater space offered by reduced drudgery while adhering to the prevalent norms of not venturing far from home base, a baby step in the journey of regaining complete agency over one’s life?

Limaye is Assistant Professor, and Trivedi is Associate Professor, Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune. Views are personal

Leave a Comment