Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, is a degenerative brain disease linked to repeated head trauma. The condition first gained attention in high-impact sports, such as football and boxing, but it has since been linked to a range of activities in which people sustain repetitive brain injuries, such as cycling and military service.

CTE was first defined in 1949 by neurologist Dr. MacDonald Critchley, but there’s still a lot scientists don’t know about it. For instance, it’s unclear how to diagnose the disease in living patients, or if certain environmental or genetic factors raise the risk of a person developing it, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

However, scientists do know that CTE is linked not only to concussions, but also to subconcussive blows — milder impacts that don’t cause any immediate symptoms.

“I’m concerned about the future of football, because we have paid a lot of attention to concussions,” said Dr. Ann McKee, director of Boston University’s CTE Center. “But it’s really the repetitive minor injuries, the ones that are asymptomatic that occur on almost every play of the game, the subconcussive hits — that’s the big problem for football.”

Related: Lab-grown ‘minibrains’ help reveal why traumatic brain injury raises dementia risk

What causes CTE?

CTE develops following repeated head injuries, although the exact number of traumas or overall time in which the injuries occur seem to vary person-to-person. The risk of CTE is cumulative, meaning it increases with more years of exposure to head trauma, McKee said.

Risk factors include the severity and frequency of head impacts and the age at which the head injuries began, with research indicating that younger people may be more vulnerable due to their developing brains.

“Kids’ brains are developing,” McKee said. “Their heads are a larger part of their body, and their necks are not as strong as adults’ necks. So kids may be at a greater risk of head and brain injuries than adults.”

Scientists also believe that there is a genetic component to CTE. Research suggests that the gene variant ApoE4 plays a major role in determining CTE severity and that the variant makes a person 2.34 times more likely to develop a severe form of CTE, compared to people carrying other variants.

How does CTE change the brain?

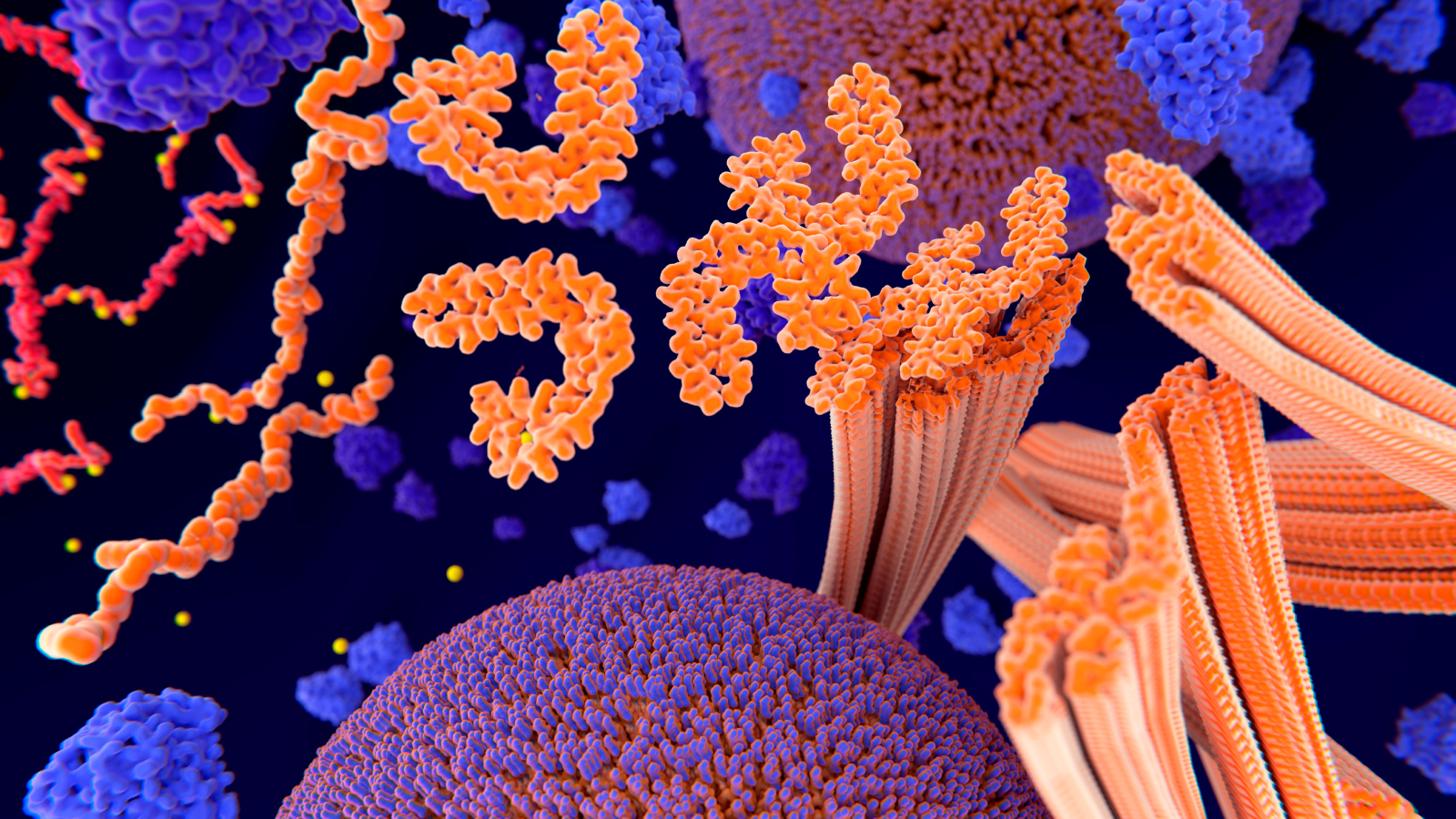

CTE is characterized by an accumulation of specific proteins in the brain, which clump together and create clusters around the organ’s small blood vessels. These proteins, called hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, also build up in people who have Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

However, the tau in CTE is distinct because it forms in specific patterns, often starting in the grooves of the brain, where repetitive head impacts cause the most stress. Unlike Alzheimer’s, where tau spreads more evenly across the brain, CTE’s tau clusters are tied directly to areas affected by trauma, making it unique to brain injuries.

Brain atrophy, or a loss of volume, is also seen in people with CTE and is thought to be driven by the tau buildup. The aggregation disrupts normal brain cell function, eventually causing neurons to die.

However, researchers don’t know how repetitive head trauma might trigger tau buildup in the first place. Some studies hint that viruses in the brain may play some part in the chain reaction.

What are the symptoms of CTE?

Early symptoms associated with CTE can appear in people’s 20s, according to the Concussion Legacy Foundation. However, although these symptoms can precede a CTE diagnosis, it’s not clear whether they’re caused by the disease itself or by other effects of head trauma. These early symptoms can include depression, anxiety, impulse control issues and aggression.

Later symptoms most often appear in a person’s 60s or 70s, but can show up in midlife for some. These symptoms include issues with judgment, short-term memory and executive functions, such as planning and reasoning. These symptoms may worsen steadily or they might stabilize for a time before later becoming worse. CTE has also been tied to sleep problems.

In advanced cases, CTE can lead to severe cognitive decline, resembling dementia.

How is CTE diagnosed?

Currently, CTE can only be definitively diagnosed after death through an autopsy, in which pathologists identify tau tangles in brain tissue.

To tentatively diagnose the condition in living individuals, doctors evaluate the patient’s clinical symptoms and history of repetitive brain injuries, as well as perform brain scans to rule out other conditions.. However, the symptoms of CTE overlap with those of other conditions, making early diagnosis challenging.

Efforts are underway to develop diagnostic tools for living patients with CTE. Researchers are exploring advanced brain scan techniques and markers of CTE that could be detected in blood tests. Developing reliable methods to diagnose CTE before death is essential for taking steps to prevent further injuries and creating effective CTE treatments in the future.

Related: Even mild concussions can ‘rewire’ the brain, possibly causing long-term symptoms

How is CTE treated?

Currently, there is no standardized treatment for CTE, meaning there is no cure. Instead the focus is on managing symptoms of the disease. This might include supportive therapies targeting specific symptoms, such as headache, lack of sleep, depression or anxiety, as well as lifestyle modifications to improve mood symptoms, for example.

Which sports and activities are most associated with CTE?

Contact sports like football, boxing and ice hockey have the highest documented rates of CTE of any sports. The disease particularly affects athletes with long careers or roles involving frequent head impacts. For example, football offensive linemen and hockey enforcers are at higher risk, compared with other positions.

But participation in certain sports isn’t the only risk factor. For example, military veterans who were previously exposed to blast injuries are also vulnerable to CTE, as are individuals who experience repeated trauma due to intimate partner violence.

In addition, recreational activities, such as motorcycle racing and bicycling, can pose a risk, as can playing high-impact sports recreationally without proper protective gear.

Can people reduce the risk of CTE?

Awareness of CTE has spurred significant changes in how head trauma is managed in sports and other high-risk activities. Measures to reduce the risks of CTE include limiting full-contact practices in youth sports, improving helmet technology and enforcing stricter concussion protocols.

In the U.S., the age at which hockey becomes “full-contact” has been pushed back several years to enable children to develop more before learning how to hit. Hockey helmet technology has also improved over the years, with modern helmets featuring hard outer shells made of composite materials like polycarbonate to withstand high-impact collisions. In addition, the increased use of mouthguards has been associated with a 28% reduction in concussion rates among youth ice-hockey players.

And concussion-spotting in college and professional hockey has continued to improve, with all training and medical staff being fully educated in spotting and treating concussions. Standard concussion care involves physical and cognitive rest immediately following the injury. Then there’s a gradual return-to-play protocol monitored by health care or sports medicine professionals, along with symptom management to address headaches, dizziness or behavioral changes.

While no cure exists for CTE, reducing episodes of head trauma and recognizing symptoms of concussion early may theoretically slow its progression. That’s because detecting head injuries early can help improve their initial treatment and preempt “second impact syndrome,” in which a person incurs more head trauma before recovering from their initial blow. There is also ongoing research into diagnostics and treatments for CTE.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Leave a Comment