Inclusive development has become synonymous with cash handouts to the accounts of beneficiaries. After the NDA’s electoral sweep of Maharashtra in the recent Assembly elections, attributed largely to its Ladki Bahin Yojna, it is now clear that populism has come to stay as a defining feature of electoral politics.

The Yojna, costing the exchequer ₹45,000 crore annually, offers a monthly stipend of ₹1,500 to nearly 2.5 crore women in Maharashtra. The BJP had resisted the practice until now, believing that its development record alone would suffice to win votes, but having been chastised in the Parliamentary elections, has now embraced the freebies bandwagon.

In Odisha, the BJP implemented the Subhadra scheme to provide one crore women direct financial assistance of ₹50,000 over five years at a cost of ₹55,825 crore.

West Bengal has perhaps the largest number of such handout schemes, covering practically every section of voters, including its much-touted Lakshmir Bhandar under which 2.2 crore women get ₹1,200 or ₹1,000 every month in their accounts, depending on whether they belong to the SC/ST category or not.

Assembly elections in Karnataka, Himachal Pradesh and Telangana, and earlier in Punjab, were won by the opposition parties by promising several such guarantees. Digital Jan-Dhan connectivity has made implementing these promises involving direct benefit transfer a seamless process, and voters know that unlike in the past, parties would now implement them. After all, unlike implementing developmental schemes and delivering their benefits to a large section of population which require many glitches to be fixed, transferring cash is rather easy.

Struggling to find resources

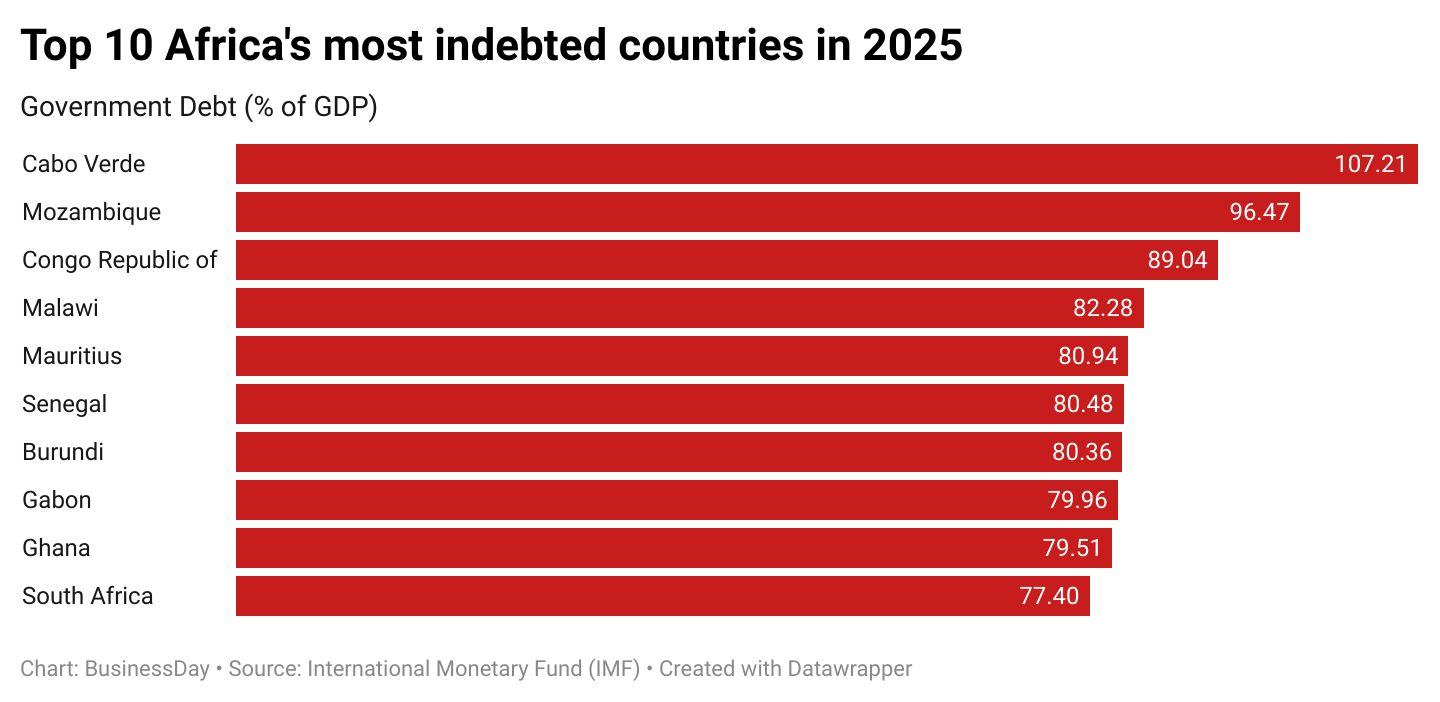

But these handouts are pushing public debt to unsustainable levels. Many States are now struggling to find resources even to pay salaries to their employees, like in Himachal Pradesh whose debt ratio has soared to 42 per cent of GSDP.

In Karnataka, Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge recently chided Chief Minister Siddaramaiah for making electoral promises he cannot fulfil — Karnataka’s fiscal deficit is projected to swell from ₹46,622 crore, or 2 per cent of GSDP in FY23, i.e. before the election, to ₹82,980 crore, or 3 per cent of GSDP, in FY25. High fiscal deficit means higher cost of capital for private borrowers which inevitably leads to flight of capital. This has happened in Karnataka.

The State’s total FDI has fallen from $22 billion in 2021-22 to only $6.57 billion in 2023-24, benefiting Gujarat in the process. High borrowing also imposes additional burden in the form of higher interest which curtails developmental expenditure, additionally causing higher inflation. All these impact growth, and for the first time in many years, in FY24, Karnataka’s real growth of 6.6 per cent fell below the national growth rate of 7.2 per cent.

The need for more money is making some States resort to practices which can be perilous for public finance. Sometimes they force their public sector entities to raise loans on the basis of government guarantees to finance welfare schemes which are not budgeted and hence do not add to fiscal deficits, but these loans are nevertheless serviced from State revenues.

Sometimes, even the future revenues are pledged to an escrow account to repay these loans, as in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala or MP, which is an unconstitutional practice, and hides such liabilities from public eye. Some States are even levying certain cess and tying their proceeds for servicing these loans, while the Constitution allows only the Centre to levy a cess. We can neither expect politicians to restrain their promises, nor voters to punish them for irresponsibility.

Institutions like the Election Commission and even the Supreme Court have proved ineffective here. Under Article 150 of the Constitution, CAG is responsible for prescribing the format of government accounts, which includes mandatory disclosures. CAG can force the governments to disclose risky, extra-budgetary practices. That may be a small improvement to begin with.

The writer, a former Director-General with CAG of India, is currently a Professor of Practice at the Arun Jaitley National institute of Financial Management. Views are personal

Leave a Comment