A new discovery about a special quantum material could help advance quantum computers, sensors, and other futuristic technologies.

Scientists from the University of Regensburg in Germany and the University of Michigan (U-M) have shown that a material called chromium sulfide bromide can trap tiny quantum information carriers, known as excitons, in a single line.

Chromium sulfide bromide is exciting for researchers because it can store and process quantum information in several ways—using electricity, light, magnetism, and vibrations.

This makes it a potential “miracle material” for quantum technology.

Professor Mackillo Kira from U-M explains, “This material could be used to build quantum devices where information is processed by electrons, stored using magnetism, transferred by light, and adjusted with vibrations.”

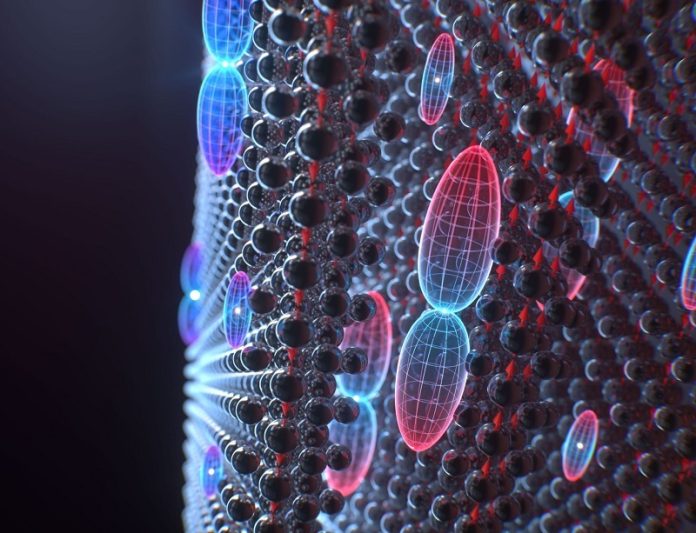

Excitons are special quantum particles that form when an electron in a material moves to a higher energy state, leaving behind a “hole.”

This electron-hole pair acts as a single unit—an exciton. Normally, excitons move freely in all directions. However, the researchers found that the magnetic properties of chromium sulfide bromide can control their movement in an interesting way.

At very cold temperatures (below -222°F or 132 Kelvin), the layers of this material become magnetized in a special way called antiferromagnetism, where the magnetic direction flips between layers.

In this state, excitons get trapped in just one layer, and within that layer, they can only move along a single line—essentially in one dimension. This is important because it helps quantum information last longer by preventing excitons from colliding and losing data.

When the temperature rises above 132 Kelvin, the magnetism disappears, and excitons become free to move in three dimensions again. This ability to switch between confined and free movement makes chromium sulfide bromide highly useful for future quantum technology.

The research team, led by Professor Rupert Huber from the University of Regensburg, used ultrafast laser pulses—lasting just 20 quadrillionths of a second—to create excitons in the material.

By using a second laser, they nudged the excitons into different energy states and noticed something surprising: the excitons had two different energy levels instead of one. This unusual effect, called fine structure splitting, happens because of the material’s magnetism.

The researchers now want to explore whether excitons, which are based on electric charge, can be converted into magnetic excitations, which use electron spins. If successful, this could create a new way to transfer quantum information between electricity, light, and magnetism, leading to faster and more efficient quantum devices.

This research was supported by institutions in Germany, the U.S., and the Czech Republic, including funding from the National Science Foundation and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Leave a Comment