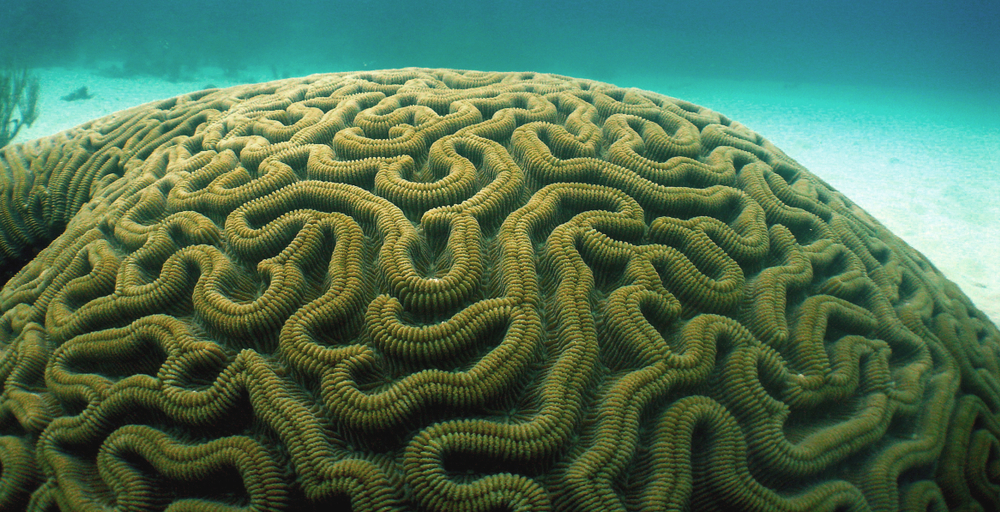

If you’re swimming across a thriving coral reef, you may mistakenly believe you floated upon a giant underwater human brain.

Brain coral is a hard coral, also known as a stony coral or reef builder. They cluster into colonies and ultimately create the foundation for a reef to form, giving soft corals and many other marine species a place to call home.

These magnificently grooved creatures, from which they get their name, are key parts of a healthy reef.

How Brain Coral Got Its Name

Hard corals like brain corals aren’t plants or even one large animal. They are made up of individual polyps – related to jellyfish and anemones – that group together, making use of calcium and carbonate ions to create a calcium carbonate skeleton. Most of the bulk of the coral is made up of this calcium-based frame.

Brain coral stands out because of its intricate, brain-like, patterns that weave across the surface. That’s because, unlike in other hard coral species, the polyps join rather than stand alone. This is true communal living, as the polyps can share food and nutrients with others in the colony.

There are around 50 species of brain coral – under the families’ Mussidae and Merulinidae – and altogether there are over 3,000 species of hard coral.

One species, the boulder brain coral, is enormous in size and it can become a solid part of the reef once it dies. Another species looks more cerebral than others. The grooved brain coral – Diploria labyrinthiformis – is found across the Caribbean and the Pacific. It can grow to about six feet (or two meters) in size and is hard to miss.

Read More: There is Still Time to Save the Coral Reefs

Living in Vibrant Colors

Coral polyps form a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae, a kind of algae, that lives within them. That’s where they get their often striking and vibrant colors.

Brain coral, for example, is colored brown, yellow, and grey. The open brain coral species is particularly stunning since it is sometimes blue and red.

When coral suffers stress, either caused by warm temperatures or a significant change in their environment, it can eject the zooxanthellae within it. This turns the coral completely white in a process known as bleaching. It isn’t death for the coral and it can bounce back, but it leaves it far more vulnerable.

Some species – such as the grooved brain coral and boulder brain coral – can grow up to and beyond six feet in diameter. But they take many years to achieve that feat, growing at a rate of only a few millimeters each year. They have the time to do so as these colonies can live for an estimated 900 years.

Coral Reproduction

To reproduce, many brain coral species release bundles of eggs and sperm several times into the surrounding waters each year. These are then caught by other polyps and are used to fertilize eggs throughout the colony.

Researchers working in the Caribbean found that D. Labyrinthiformis reproduced six times over as many months.

“This is the largest number of reproductive events per year ever observed in a broadcast-spawning Caribbean coral species,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Read More: How Volunteers Are Helping Keep Coral Reefs Alive

Threats Against Brain Coral

Brain corals are vitally important parts of marine ecosystems but some face extinction. One report earlier this year found that 44 percent of reef-building corals are now classified as endangered.

One species, the Chagos brain coral found only in the Chagos Archipelago, is considered critically endangered after once thought to be extinct.

Though coral may face many threats across the globe, climate change and increasingly common bleaching events are amongst the most severe. Protecting these curious and unique brains of the ocean is needed if reefs around the world are to remain healthy.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Sean Mowbray is a freelance writer based in Scotland. He covers the environment, archaeology, and general science topics. His work has also appeared in outlets such as Mongabay, New Scientist, Hakai Magazine, Ancient History Magazine, and others.

Leave a Comment