by Jonathan Latham, PhD and Allison Wilson, PhD

One of the very earliest scientific papers from the COVID-19 pandemic era now has over 11,000 citations. Appearing in the scientific journal Nature on February 3rd 2020, Zhou et al., 2020 reported the genome sequence of a novel coronavirus isolated from patients with atypical pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Its senior author was leading coronavirus researcher Zheng-li Shi of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (the WIV). Along with what we now call SARS-CoV-2, her paper also reported the genome sequence of a closely related (96.2% identical) bat virus. The authors called this virus RaTG13. To this day RaTG13 is still the closest known viral genome by far to SARS-CoV-2.

RaTG13 came from the freezers of the WIV.

In one sense, there is nothing unusual about that. Researchers often have old samples stored away and the WIV has the largest collection of coronaviruses in the world. On the other hand, Wuhan is considered an unlikely locality for a coronavirus outbreak.

However, the two sentences in Zhou et al., (2020) describing RaTG13 allayed any fears:

“We then found that a short region of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) from a bat coronavirus (BatCoV RaTG13)–which was previously detected in Rhinolophus affinis from Yunnan province–showed high sequence identity to 2019-nCoV. We carried out full-length sequencing on this RNA sample (GISAID accession number EPI_ISL_402131).”

This statement clearly implied that, prior to the pandemic, WIV researchers had only ever studied a ‘short’ fragment of RaTG13, that the fragment was unpublished (since no prior description was cited), and that no recent research had been carried out on RaTG13 or its sample. Consequently, a lab leak involving RaTG13 was implausible.

But all these inferences turned out to be untrue. Zhou et al. was one of the pandemic’s key misinformation superspreaders. In August 2020, two researchers, Monali Rahalkar and Rahul Bahulikar, published a preprint in which they reported that they had accessed the underlying sequencing files for RaTG13. As first noticed by Twitter user Francisco A. de Ribeira, some were dated from 2017 and others from 2018. Moreover, these early RaTG13 sequences went far beyond a short fragment, encompassing most of the genome (Rahalkar and Bahulikar, 2020a).

In November 2020 Nature published an addendum to Zhou et al. in which Zheng-li Shi and her co-authors conceded these points. They wrote:

“In 2018…..we performed further sequencing of these bat viruses and obtained almost the full-length genome sequence (without the 5′ and 3′ ends) of RaTG13.”

Thus the RaTG13 genome sequence was mostly deciphered in 2018 and not in January 2020. Ergo, the viral genome most similar to SARS-CoV-2 was being studied at the WIV before the pandemic broke out.

But why hide this activity?

The outbreak in the Mojiang Mine

By the time of these revelations, yet other questions had arisen about RaTG13. It turned out that RaTG13 was an exact genetic match to an already published partial virus sequence called BtCoV/4991. BtCoV/4991 had been obtained by Zheng-li Shi’s group in 2013 from a mine in Yunnan Province, China (Ge et al., 2016).

Furthermore, RaTG13 and BtCoV/4991 were from the same bat anal swab sample. In other words, from the data provided, the two were indistinguishable. Thus, RaTG13 did have a publishing history, but under the name BtCoV/4991 (Bengston, 2020).

In addition to BtCoV/4991 another novel betacoronavirus was found at the same time. Their discoverers concluded the following:

“Considering that the two highly pathogenic human coronaviruses (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) in this genus [the Betacoronaviruses] originated from bats (Ge et al., 2013; Lau et al., 2013; Corman et al., 2014), attention should be particularly paid to these lineages of bat coronaviruses.” (Ge et al., 2016)

According to their own words, it would therefore be surprising had Zheng-li Shi’s group not gone on to study BtCoV/4991 aka RaTG13.

Yet the discovery of this publication trail only deepened the mystery yet further. Though never mentioned by Ge et al., the ‘abandoned’ mine (which subsequently became known as the Mojiang mine) where BtCoV/4991 was found had recently been the site of a mystery disease outbreak. In April 2012, just two and a half months before the first WIV sampling trip, six miners had become sick and three of them had died. Indeed, the mine outbreak was presumably why the WIV researchers were sampling there (and the Zhou et al. addendum later confirmed this).

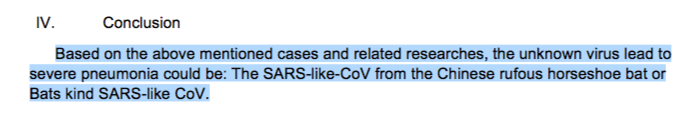

The nature of the 2012 disease outbreak became much clearer with the discovery (by an anonymous Twitter user called @TheSeeker268) of a 2013 Chinese Master’s thesis. This thesis is titled “The Analysis of Six Patients With Severe Pneumonia Caused By Unknown Viruses“. Its abstract specifically mentions a possible outbreak of SARS-like coronaviruses.

To learn more about the 2012 pneumonia outbreak, we arranged to have the Master’s thesis translated into English.

The translation yielded a cornucopia of information. This began with the fact that the author of the thesis was the doctor who supervised the testing and treatment of the miners at the First Affiliated hospital of Kunming Medical University (Yunnan Province).

According to the Master’s thesis, the miners had been shovelling bat guano. This implied that the mystery disease probably originated from bats. That, along with various test results and consultations led the author to conclude that the most likely cause of the outbreak was a coronavirus. But perhaps most startling of all the findings to emerge from the translation was that the symptoms of the miners closely resembled those of COVID-19 (Rahalkar and Bahulikar, 2020b).

The Master’s thesis thus raised a host of questions. Why did the Ge et al. 2016 publication (from Zheng-li Shi’s lab), which sampled the mine on multiple occasions, make no mention of the outbreak that caused them to be sampling there in the first place? Why did Zheng-li Shi tell Scientific American in March 2020 that the miners died of a fungal infection? Why did her Zhou et al. 2020 publication rename BtCov/4991 as RaTG13 without explanation or even referencing the earlier work on BtCov/4991 or its mine origin? Especially, given that Zheng-li Shi and her corona-colleagues in China and elsewhere have constantly warned of coronavirus spillovers from bats (e.g. Zhou et al., 2018), why did no one seemingly prove or disprove the coronavirus theory in the Master’s thesis? Are we to presume that an apparent textbook case of a zoonotic spillover, significant enough at the time to be covered by Science magazine, was in the end simply ignored?

So many interrelated errors and omissions present a conundrum. Are these concatenated oversights simply innocent happenstances? Or were they deliberate attempts to obscure the connections from RaTG13 back to BtCov/4991 and from there to the mine and thence to the mine outbreak; to thereby prevent anyone in 2020 linking SARS-CoV-2 and the mine outbreak in 2012? Is there something about the mine or the miners of deep significance to the current pandemic? If so, what?

The value of the PhD thesis

Given that the broader context of the pandemic origin is the failure of a plausible zoonotic origin scenario to emerge (Quay, 2021; Segreto et al., 2021), we have attempted to resolve this conundrum by proposing the Mojiang Miners Passage theory of the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

The theory was stimulated chiefly by two observations. The first was that some of the miners with the mystery disease were ill for about five months (April to September, 2012). The second key observation was the assertion in the Master’s thesis that diagnostic samples taken from four of the miners were sent to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

What we proposed, in short, is that the miners contracted one, or maybe multiple, RaTG13-like bat coronaviruses in the mine. The long hospitalization of the miners enabled the initial bat virus to evolve into a human coronavirus by providing conditions similar to extended viral passaging. The diagnostic samples sent to the WIV therefore contained a humanised virus and we proposed it was similar, or even identical, to SARS-CoV-2. Virus isolation, or virus culture in human or other cells, or perhaps even Gain-of-Function type experiments, then permitted this virus to later escape from the WIV in late 2019.

Given all this, a very significant unresolved question becomes: What tests were done on the samples taken from the miners and sent to the WIV? What were the results? The answers are important not only for the Mojiang Miners Passage theory but also for other explanations of the pandemic origin. For example, other lab escape theories have proposed that RaTG13 (or a similar unpublished genome) was the likely backbone for Gain-of-Function research (see Sirotkin and Sirotkin, 2020; Segreto and Deigin, 2020; Segreto et al., 2021; Kaina, 2021). But it is also possible that a virus extracted from the miners was the starting point.

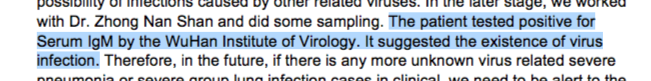

According to the Master’s thesis, Prof. Nanshan Zhong advised SARS testing and samples from four miners were therefore sent to the WIV. These tested positive for coronavirus in an IgM antibody test (See Fig. 1).

In their November addendum Zheng-li Shi and her colleagues at the WIV confirmed receiving thirteen serum samples–taken at approximately monthly intervals in 2012–from four of the hospitalised miners. But here there is a major discrepancy. Referring to the miner serum samples, the addendum states:

“To investigate the cause of the respiratory disease, we tested the samples using PCR methods developed in our laboratory targeting the RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of Ebola virus, Nipah virus and bat SARSr-CoVRp3, and all the samples tested negative for these viruses. We also tested the serum samples for the presence of antibodies against the nucleocapsid proteins of these three viruses, and none of the samples gave a positive result. Recently, we retested the samples with our validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) against the SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) nucleocapsid protein–which has greater than 90% amino acid sequence identity with SARSr-CoVRp3–and confirmed that these patients were not infected by SARS-CoV-2.” (Zhou et al., 2020, addendum)

The implication is that, though various tests were performed at the WIV, SARS-CoV-2 was not found and no evidence for any other coronavirus was found either.

This obviously contradicts the Master’s thesis.

The difference between these two positions is crucial. If a coronavirus of any kind was found in the miners’ samples it would likely alter our whole understanding of the pandemic origin.

This is because every possible effort would surely have been made to identify it, grow it in cultured human cells, sequence its genome, characterise its infectivity, and much more. There are two primary reasons for this.

First, discovering a coronavirus infection in the miners would triumphantly vindicate the basic research premise of Zheng-li Shi and the WIV. Their pitch is that bat coronaviruses are dangerous pathogens that may at any moment jump to humans and other animals.

Second, a novel coronavirus in the miners would represent a veritable research bonanza: a highly lethal zoonotic disease outbreak caught in the act.

By the same token, if a coronavirus was found in the 2012 miners’ samples it would surely also mean that subsequent research, presumably at the WIV, has been concealed.

This then is the background to our interest in any credible document containing further evidence that the research trail from the miners did not go cold after the 2012 outbreak.

The PhD thesis of Canping Huang

For many months, a scientific document has been shared on the internet that appears to shed much light on the fate of samples taken from the mine and the miners, as well as the broader context. It is a translation of a Chinese PhD thesis originally written in 2016. Like the Master’s thesis it also was found on the Chinese thesis database by @TheSeeker268. Its English title is “Novel Virus Discovery in Bat and the Exploration of Receptor of Bat Coronavirus HKU9”. (Download the Chinese PhD thesis here)

The author of this thesis is Canping Huang, who was a student of Gao Fu. Gao Fu is an important virologist known in the West as George Gao. In 2017 he was appointed head of China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China’s CDC.

The direct relevance of the Canping Huang thesis, however, is that the author is one of relatively few researchers documented to have sampled the Mojiang mine for bat viruses.

Previously, a provisional and partial translation of this thesis was generated, using Google translate, by the previously mentioned Francisco A. de Ribera. Using this earlier version as a guide, we have organised a professional and expanded translation.

This new version focuses on the parts of the thesis most relevant to the origin story of SARS-CoV-2; in particular, Chapter 3 titled: Initial investigation of the causes of unexplained severe pneumonia incidents related to an abandoned mining cave found in Mojiang Hani Autonomous County, Yunnan Province.

The Canping Huang thesis substantiates several aspects of the Mojiang Miners Passage theory. But perhaps the most significant of all its statements is that samples from four of the miners were tested at the WIV for IgG antibodies against the SARS virus. According to the PhD (see Fig. 3), all samples were positive. (This test is distinct from the IgM test mentioned in the Master’s thesis).

The logical interpretation of an IgG antibody test for SARS giving a positive result in 2012 is that the miners were infected with a coronavirus, presumably a SARS-related one. It is highly unlikely, however, that the miners had SARS itself, since the SARS virus had not been observed since 2003. Moreover, the original SARS outbreak was in Guangdong province, far from the Mojiang mine. Thus, the miners presumably were infected with a virus similar, but not identical to, SARS, i.e. a novel coronavirus. Most importantly, this is the conclusion reached also by the Master’s thesis (see Fig 4).

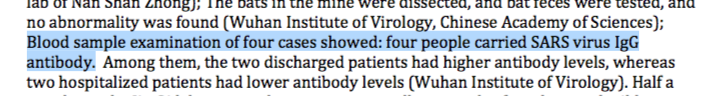

What adds particular credibility to the PhDs’ claim are its specifics. According to Canping Huang, of the four miners:

“two discharged patients had higher antibody levels, whereas two hospitalized patients had lower antibody levels”.

Such details imply that the PhD’s assertion of positive SARS tests is not a simple mistake, nor based on mere hearsay. Rather, as the mysterious pneumonia outbreak was author’s reason to sample the mine (see Chapter 3.), these results had crucial significance to the thesis; just as they would have had to his supervisor and the Chinese CDC. Furthermore, a PhD is a peer-reviewed document. It has to be accepted by the supervisor and a committee. If the tests and/or the positive results were cited in error then these were multiple errors with multiple parents.

Indeed, in an interview with French TV (at 18:23), George Gao was asked about the antibody tests of the miners and he confirmed the positive tests.

Since it is not easy to dismiss, this assertion of multiple positive tests is a fact of great significance. As we and others have suggested, it seems likely that the miners had COVID-like symptoms because they were infected with a SARS-like coronavirus.

If so, researchers at the WIV have attempted to hide that diagnosis.

Is it time for an addendum to the addendum?

Ideally, one would seek to clarify precisely where the assertions in the PhD thesis (positive IgG test of four patients for SARS) and the Master’s thesis (positive IgM tests for an unspecified number of patients) contradict those in the Zhou et al. addendum.

However, although it purports to resolve the issues, the addendum is a complete mismatch with the questions raised by either thesis. Firstly, nowhere does the addendum positively state that no virus or no coronavirus was found in the miners’ serum samples.

Secondly, the addendum does not mention a SARS test. It mentions instead two different tests for SARSr-CoV-Rp3 (a bat virus related to SARS), and one test for SARS-CoV-2. It is presumably possible that the PhD and the Master’s and George Gao were mistaken and conflated tests for SARSr-CoVRp3 with ones for SARS itself (or perhaps were misinformed); but this does not alter the situation fundamentally since, contra the addendum, all three sources claim the results were positive.

Failure to directly address the principal questions spotlights a noteworthy additional defect of the addendum. It lacks the key accoutrements of a scientific publication. The addendum asserts the results of three tests but their methods are not fully described, nor are the materials and reagents. The results, including controls, are also not shown. Importantly too, the eight similar viruses mentioned as being found along with RaTG13/4991 are neither referenced nor specified by name, even though their genomes may be crucial for tracing the pandemic’s origins. It is unscientific and ultimately somewhat ridiculous for Nature to publish an addendum making controversial, claims that are crucial to understanding the origin of a global pandemic costing millions of lives, but make meaningful independent scrutiny of those claims impossible.

Nevertheless, the addendum should raise yet more eyebrows. When Canping Huang identified and isolated novel viruses from his bat samples, the methods he used, in Chap 3., were pan-coronavirus primers in PCR experiments and viral metagenomics in the form of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). Yet neither method is mentioned in the addendum. The tests described by the addendum are not worthless, but they are also not best practice when the question is how to detect a mystery coronavirus. Apparently, the WIV, a world-leading institute, did not apply the most sensitive or effective available methods in this crucial and unprecedented instance of a zoonotic jump caught in flagrante.

China is a leader in gene sequencing technology but one could perhaps imagine that in 2012-13 NGS was unavailable to Zheng-li Shi. However, we know that she sent samples to Beijing for NGS as early as 2011 (Ge et al., 2012). In any case, it is available today. When Zheng-li Shi’s group first identified the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus from patients in Wuhan they used pan-coronavirus primers. Next they used metagenomic sequencing to decipher its genome (Zhou et al., 2020). We know too that the miners’ samples are apparently not depleted since the addendum claims to have ‘retested’ them ‘Recently’.

Additionally, there are now powerful methods for retrieving degraded and low abundance genetic material, even from biological samples millions of years old (e.g. Dabney et al., 2013). In 1997 the Spanish Flu influenza genome was reconstructed from preserved human tissues (Taubenberger et al., 1997). If necessary, such methods could surely be applied to any of the extant samples from the miners.

The PhD thesis translation prompts still further questions about the addendum and the miners’ samples, For example, we need to know more about the 13 serum samples. What dates were they taken on and which miners did each come from? Also, the Master’s thesis mentions extraction of the thymus of patient 4, while both it and the PhD mention that throat swabs were taken (PhD, p. 82). According to both theses, such samples were sometimes sent to other institutions. In many cases, these samples probably represent better opportunities to collect a coronavirus and demonstrate a virus spillover than does a serum sample. Did the WIV receive or request other samples? Were tests performed on them? If so, what were the results? Answers, one hopes, along with data to support them, will perhaps be provided in a second addendum.

In the final analysis this situation is ultimately quite simple: three sources (the Master’s thesis, Canping Huang’s PhD and George Gao) clearly and credibly contradict the implication of the addendum on the key question of whether a coronavirus was detected in the miners’ serum samples. Moreover, two of these sources predate the pandemic. Unlike the WIV authors, no case can reasonably be made that the two thesis authors were motivated by self-preservation as a consequence of the pandemic. The WIV authors, in contrast, have a track record of misleading statements and clear omissions in connection with the miners outbreak and RaTG13; hence the need for the original addendum.

Further revelations of the Canping Huang PhD thesis

The Canping Huang PhD contains other data and important statements. It corroborates the Master’s thesis, lends significant support to the Mojiang Miners Passage theory, and further contradicts the accounts of researchers from the WIV.

1) Canping Huang was a virologist. Together with a team assembled by the Chinese CDC, he searched the Mojiang mine specifically for viruses. In all, at least four independent teams of Chinese virologists (some representing multiple labs) searched the Mojiang mine.

Beginning in July 2012, researchers from Zheng-li Shi’s lab at the WIV visited the mine up to seven times (WHO report, Annex, p131). In it they found several hundred Alphacoronaviruses and ten Betacoronaviruses [the addendum states nine Betacoronaviruses but it appears to omit HpBtCoV/3740-2, which was also found there (Ge et al., 2016)] (Zhou et al., 2020 addendum). Of these, the Betacoronaviruses are the most significant because RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 are Betacoronaviruses. Later in 2012, researchers from Peking Union Medical College and the Institute of Pathogen Biology in Beijing also took samples. They identified a paramyxovirus in rats from the mine (Wu et al., 2014). The third team was a group from the University of Hong Kong who found Alphacoronaviruses in the mine (Lau et al., 2015). The fourth was Canping Huang in 2014. This intense sampling activity shows that prominent Chinese researchers like George Gao suspected that the causative agent of the mine outbreak was a virus, and were still hunting for clues in 2014. Nevertheless, the March 2021 WHO report, like the earlier Scientific American interview, attributes the miners’ illnesses to a fungal infection (WHO Annex, p131). However, it should be emphasized that, once again, this mention of a fungal origin by the WHO is not supported by any data or cited evidence. Nor is there any suggestion that fungal biologists investigated the outbreak. The case for a fungal outbreak is therefore very weak.

2) Canping Huang and his colleagues caught and killed 87 bats and one rat. This sampling bias suggests bats were still considered the most likely source of the miners’ disease in 2014.

3) In these bats, Canping Huang found four astroviruses, one bocavirus and two Alphacoronaviruses. This indicates that bats with coronaviruses continued to be present in the mine in 2014, two years after the outbreak. More importantly, his use of degenerate (i.e. all-purpose) PCR primers designed to amplify coronavirus genomes (see Chapter 3 of the PhD) demonstrates that Canping Huang was actively searching specifically for coronaviruses (and also for certain other viruses too).

4) The PhD also states that blood samples from the miners were sent to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Prior to the November Zhou addendum, only the Master’s thesis made such a claim. Thanks to Canping Huang’s thesis, three independent sources agree that serum/blood samples were sent to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

5) The thesis also confirms important statements in the Master’s thesis that samples from the infected miners were sent to laboratories across China. According to the PhD:

“In order to analyze the pathology and the cause of the disease, the Chinese Yunnan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, other medical centers and other research labs collected samples from the patients, bats, rats and the environment. The blood samples of four cases showed that: four patients’ throat swabs and whole blood samples were negative for SARS coronavirus*, epidemic hemorrhagic fever, Dengue fever (type 1-4), epidemic encephalitis type B, flavivirus and alphavirus pathogen nucleic acid tests (Chengdu Military Region for Disease and Control). The blood samples of four of the cases, and from four other people who had been to the cave yet had no symptoms, all showed no abnormal results (Guangdong, lab of Nan Shan Zhong); The bats in the mine were dissected, and bat feces were tested, and no abnormality was found (Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences)……Half a year later, the Jin Qi lab went to the same cave to collect samples from bats and wild rats and tested for pathogens.”

*Authors note: A negative test for SARS, performed soon after admission of the miners to hospital, is also mentioned in the Master’s thesis, which largely discounts its results.

This quite lengthy list of interested laboratories goes beyond those listed in the Master’s thesis, but is not surprising. A lethal disease outbreak originating from bats with a probable viral aetiology is not an everyday occurrence. The previous one in China was declared a pandemic: the first SARS outbreak in 2002. Hence, top virology labs in China, such as those of George Gao, Zhong Nanshan, Zheng-li Shi and Qi Jin became involved in investigating the outbreak.

We are nevertheless left with a mystery, which the Canping Huang thesis deepens considerably. Why, given this strong interest, were only two quite minor scientific papers ever published that mentioned the mine, of which only one mentioned the outbreak (Wu et al., 2014; Ge et al., 2016)? Especially since no alternative cause for the outbreak was found.

Undisclosed research on emerging infectious diseases in China

Ever since the first SARS outbreak, Chinese virologists have very actively searched for potential human zoonotic pathogens, especially coronaviruses (e.g. Lau et al., 2015; Latinne et al., 2020). A “major project” called “Discovery of Zoonotic Pathogens and Study of its Pathogenicity to Humans” was funded by the National Science Foundation of China for this specific purpose. This programme was established in 2012, the year of the mine outbreak, and included Zheng-li Shi as one of its principle investigators.

There are strong signs that plenty of this emerging infectious coronavirus research remains unpublished, even those parts that are highly connected to the origins of the pandemic. For example, Chapter 3. of Canping Huang’s thesis was never published or otherwise made available. Though he identified two Alphacoronaviruses in the Mojiang mine and obtained partial genome sequences, he did not show them. They are not in the thesis itself nor does he seem to have deposited them in any public database.

A key example is that Zheng-li Shi also possesses unpublished coronavirus genomes from the mine. These include at least eight other very closely related Betacoronaviruses that she has featured in several recent oral presentations and for which she has at least partial genome sequences. These are called Ra7909, Rst7896, Rst7905, Rst7907, Rst7921, Rst7924, Rst7931, and Rst7952. These genomes, if published, would approximately double the number of published genomes in the SARS-CoV-2 phylogenetic clade, which is the phylogenetic group containing all the closest relatives of SARS-CoV-2. The information contained in these genomes would doubtless be extremely valuable for understanding the ancestry of SARS-CoV-2. It is therefore remarkable that they remain unpublished over a year after the Wuhan outbreak. Similar points can be raised about the more distantly related Betacoronavirus HpBtCoV/3740-2 also identified from the Mojiang mine by her group (Ge et al., in 2016). The only publicly available information on this virus is a short fragment deposited in a database five years ago.

Adding to this list of unpublished research is a very interesting recent preprint by a group of independent researchers. It is titled “Unexpected novel Merbecovirus discoveries in agricultural sequencing datasets from Wuhan, China” and it reports the existence of a series of hitherto unpublished full- and partial-length Betacoronavirus genome sequences (Zhang et al., 2021). These genomes were uncovered by examining Chinese sequencing datasets (mostly originating in Wuhan) uploaded to the NCBI genome repository. These datasets were then searched by the authors for coronavirus sequence contamination. Coronavirus sequence reads found in these datasets were then assembled by the researchers into whole or partial coronavirus genomes. What such searches reveal are either instances of biological contamination (e.g. stray viruses in biological cultures or whole organisms) or stray sequences resulting from methodological contamination during sequencing–usually sample mix-ups of a kind known as index hopping.

Among the findings made by these researchers were a full-length novel HKU5-related coronavirus and an apparent full-length infectious clone of a novel HKU4-related coronavirus. These are both MERS-related coronaviruses. These were not the only coronaviruses they found and therefore what the data suggests is that, in China, numerous labs are isolating, culturing, or otherwise studying unpublished coronaviruses.

These examples of unpublished viruses may only be the tip of an iceberg. What they and the examples that preceded it highlight, however, is the importance of accessing the WIV’s virus databases that were taken offline at the outset of the pandemic. These are where unpublished viral sequences from the WIV and elsewhere were stored. The need to know which viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 were being studied by scientists in Wuhan in 2019 is urgent.

Future directions for lab origin investigations

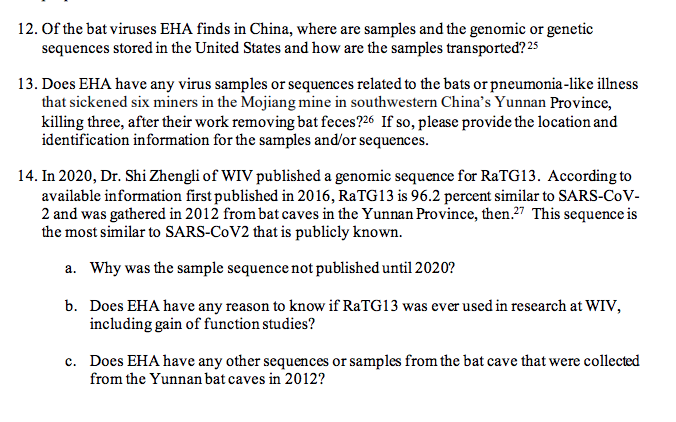

Given the pattern of evidence that is accumulating it is encouraging that members of the US Congress have written to Peter Daszak of the EcoHealth Alliance with a list of key questions about the relationship of the EcoHealth Alliance with the WIV. This letter in particular requests access to virus samples held by them and especially those samples related to the Mojiang mine at the time of the outbreak (see Fig. 5).

The EcoHealth Alliance has had funding and active working relationships with coronavirus researchers at the WIV for over a decade. Given the obstructive role it played in resisting investigations of laboratory origins, any effort to get answers from the EcoHealth Alliance deserves wide support. The Congressional letter is constructive in that it combines a precise focus on the key scientific data gaps with a broad view of accountability. In the final analysis, exactly who might have spilled the SARS-CoV-2 virus is not necessarily more important to know than who funded them and who conceived and instigated the research.

The Congressional letter raises many questions pertinent to any investigation of the virus’ origin. What is altered by the revelations of the PhD is to render much more compelling the probability, first asserted in the Master’s thesis, that there was a coronavirus in medical samples taken from the miners. This in turn serves to underline the obvious inconsistencies and omissions of Zhou et al. 2020 and especially its addendum. These flaws make the likelihood that the Mojiang mine played a key role in the COVID-19 outbreak seem ever more plausible and the need to obtain samples and sequences still more urgent.

All origin possibilities should be considered and fully investigated. But in our view, the Mojiang Miners Passage origin theory is particularly valuable because it is a scientifically testable hypothesis. If a transparent and independent analysis of samples from each of the miners were carried out it should show whether or not they had a coronavirus infection. If present in the samples a coronavirus genome sequence (even a quite short fragment) would likely definitively prove, or disprove, the theory beyond any reasonable doubt.

According to the WHO origin report, Chinese virologists have scoured the country for bat-derived coronaviruses. But at the same time, the WIV and the EcoHealth Alliance have not shared what is apparently in their own freezers and databases. The obstacle therefore seems not to be one of ability to share data but of willingness. But such obvious reticence carries a risk. The less openness scientists at the WIV and the EcoHealth Alliance show and the more they appear to dodge the key questions, the more the suspicion will unavoidably grow of their collective culpability for whatever really happened in Wuhan in late 2019.

The authors would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of Francisco A. de Ribera in preparing this article.

References

Andersen, K. G., Rambaut, A., Lipkin, W. I., Holmes, E. C., & Garry, R. F. (2020). The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nature medicine, 26(4), 450-452.

Dabney, J., Knapp, M., Glocke, I., Gansauge, M. T., Weihmann, A., Nickel, B., … & Meyer, M. (2013). Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of a Middle Pleistocene cave bear reconstructed from ultrashort DNA fragments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(39), 15758-15763.

Ge, X., Li, Y., Yang, X., Zhang, H., Zhou, P., Zhang, Y., & Shi, Z. (2012). Metagenomic analysis of viruses from bat fecal samples reveals many novel viruses in insectivorous bats in China. Journal of virology, 86(8), 4620-4630.

Ge, X. Y., Wang, N., Zhang, W., Hu, B., Li, B., Zhang, Y. Z., … & Wang, B. (2016). Coexistence of multiple coronaviruses in several bat colonies in an abandoned mineshaft. Virologica Sinica, 31(1), 31-40.

Huang, C., Liu, W. J., Xu, W., Jin, T., Zhao, Y., Song, J., … & Gao, G. F. (2016). A bat-derived putative cross-family recombinant coronavirus with a reovirus gene. PLoS pathogens, 12(9), e1005883.

Kaina, B. (2021) On the Origin of SARS-CoV-2: Did Cell Culture Experiments Lead to Increased Virulence of the Progenitor Virus for Humans? In Vivo 35 (3) 1313-1326; DOI: https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.12384

Latinne, A., Hu, B., Olival, K. J., Zhu, G., Zhang, L., Li, H., … & Li, B. (2020). Origin and cross-species transmission of bat coronaviruses in China. bioRxiv.

Lau, S. K., Feng, Y., Chen, H., Luk, H. K., Yang, W. H., Li, K. S., … & Woo, P. C. (2015). Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus ORF8 protein is acquired from SARS-related coronavirus from greater horseshoe bats through recombination. Journal of virology, 89(20), 10532-10547.

Li, C. X., Shi, M., Tian, J. H., Lin, X. D., Kang, Y. J., Chen, L. J., … & Zhang, Y. Z. (2015). Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. elife, 4, e05378.

Liu, Q., Xu, W., Lu, S., Jiang, J., Zhou, J., Shao, Z., … & Xu, J. (2018). Landscape of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in China: impact of ecology, climate, and behavior. Frontiers of medicine, 12(1), 3-22.

Mazet, J. A., Wei, Q., Zhao, G., Cummings, D. A., Desmond, J. S., Rosenthal, J., … & Daszak, P. (2015). Joint China-US call for employing a transdisciplinary approach to emerging infectious diseases. Ecohealth, 12(4), 555-559.

Quay MD PhD, S. C. (2021). A Bayesian analysis concludes beyond a reasonable doubt that SARS-CoV-2 is not a natural zoonosis but instead is laboratory derived. (Preprint).

Rahalkar, M., & Bahulikar, R. (2020a). The Anomalous Nature of the Fecal Swab Data, Receptor Binding Domain and Other Questions in RaTG13 Genome. (Preprint)

Rahalkar, M. C., & Bahulikar, R. A. (2020b). Lethal pneumonia cases in Mojiang miners (2012) and the mineshaft could provide important clues to the origin of SARS-CoV-2. Frontiers in public health, 8, 638.

Sallard, E., Halloy, J., Casane, D., Decroly, E., & van Helden, J. (2021). Tracing the origins of SARS-COV-2 in coronavirus phylogenies: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 1-17.

Segreto, R., & Deigin, Y. (2020). The genetic structure of SARS‐CoV‐2 does not rule out a laboratory origin: SARS‐COV‐2 chimeric structure and furin cleavage site might be the result of genetic manipulation. BioEssays, 2000240.

Segreto, R., Deigin, Y., McCairn, K., Sousa, A., Sirotkin, D., Sirotkin, K., … & Zhang, D. (2021). Should we discount the laboratory origin of COVID-19?. Environ Chem Lett (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-021-01211-0

Sirotkin, K., & Sirotkin, D. (2020). Might SARS‐CoV‐2 have arisen via serial passage through an animal host or cell culture? A potential explanation for much of the novel coronavirus’ distinctive genome. BioEssays, 42(10), 2000091.

Taubenberger, J. K., Reid, A. H., Krafft, A. E., Bijwaard, K. E., & Fanning, T. G. (1997). Initial genetic characterization of the 1918 “Spanish” influenza virus. Science, 275(5307), 1793-1796.

Wu, Z., Yang, L., Yang, F., Ren, X., Jiang, J., Dong, J., … & Jin, Q. (2014). Novel henipa-like virus, Mojiang paramyxovirus, in rats, China, 2012. Emerging infectious diseases, 20(6), 1064.

Zhang, D., Jones, A., Deigin, Y., Sirotkin, K., Sousa, A., & McCairn, K. (2021). Unexpected novel Merbecovirus discoveries in agricultural sequencing datasets from Wuhan, China. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.01533.

Zhou, P., Fan, H., Lan, T., Yang, X. L., Shi, W. F., Zhang, W., … & Ma, J. Y. (2018). Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature, 556(7700), 255-258.

Zhou, P., Yang, X. L., Wang, X. G., Hu, B., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., … & Chen, H. D. (2020). A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature, 579(7798), 270-273.

Editor’s note. We welcome comments and information about the subject of this article. However, please note that the “reply” function in the comments section is not working for people without high level access to the website. There are two possible solutions for readers wanting to reply to specific comments:

1) Enter your comment but name the commenter you are responding to (if necessary with the date of their comment). Or,

2) Mail your comment to the editor: [email protected] and they will post it as a reply. Please be sure to say who/what you are replying too.

If this article was useful to you please consider sharing it with your networks.

Leave a Comment