An intelligent approach?

Feedback’s ears always prick up when we see a publication with a self-aggrandising title. So we latched with interest onto a social media post by Rebecca Sear, a demographer at Brunel University London, who noted that publisher Elsevier has “chosen new editors for Intelligence“.

Intelligence, you see, is a scientific journal that publishes studies that make “a substantial contribution to an understanding of the nature and function of intelligence”. Feedback cannot verify that the editors have been changed, because the journal’s “About” page hasn’t been updated, but it did advertise for a new editor-in-chief in January 2024. There has been a report that most of the editorial board has resigned in protest at the appointment of the new editor(s), but since that report appeared on a far-right website, Feedback is disinclined to believe it without further evidence.

Hang on, readers may be thinking. How did we get from a scientific journal replacing its editors to a far-right website? The thing is, intelligence research has sometimes been misused to justify claims of racial superiority, especially during the eugenics movement of the early 20th century. And Intelligence has published research that your racist uncle might quote approvingly.

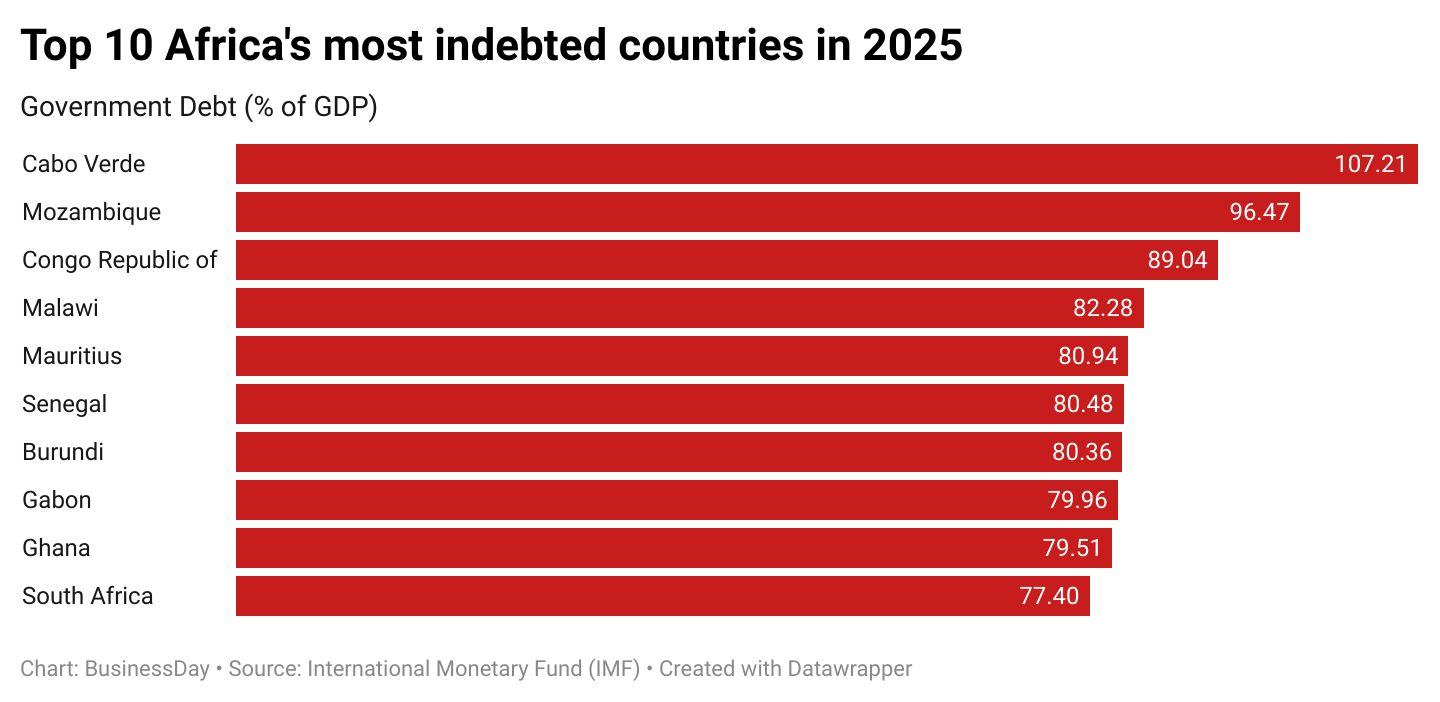

Someone at Elsevier appears to have noticed. The Guardian has reported the publisher was reviewing papers by the late Richard Lynn, who claimed to have found variations in IQ between countries – including in papers in Intelligence.

This is all getting a bit dark, so let’s move swiftly forward to the other issue with Intelligence: its apparent lack of its supposed defining trait. Sear highlighted a paper with the innocuous-seeming title “Temperature and evolutionary novelty as forces behind the evolution of general intelligence“.

Its thrust is that, when some Homo sapiens populations first migrated outside Africa, they encountered all sorts of novel conditions, like different climates. This prompted them to evolve a greater level of intelligence. What this means for African populations is left to the reader to infer.

If this all sounds like something from the bad old days of Victorian science, Feedback regrets to inform you that this paper was actually first published online in 2007. However, if you swallow your nausea and look closer, a true delight emerges.

The first issue is that the author calculates the distances populations travelled “as the crow flies”. You can’t use straight-line distances as even a first approximation for the history of human migration, which involved people journeying to the far north-east of Asia, crossing into North America and onwards to the southern tip of South America.

But it gets better. In the same sentence, the paper’s author says he calculated the distance “using the Pythagoras’ theorem”. Readers will recall that Pythagoras’ theorem only applies to flat planes and doesn’t work for curved surfaces. Yes, this study about the racial origins of intelligence is built on the assumption that Earth is flat.

With immense academic restraint, a 2009 rebuttal suggested this study might be “questionable”. Other psychologists brought the problem to the journal’s attention, only to be told that their critiques were “wholly negative and nitpicking“. The paper remains live.

Accordingly, Feedback would like to nominate the journal Intelligence for the 2025 Reverse Nominative Determinism Award.

Forty lashes

New Scientist reporter Karmela Padavic-Callaghan highlights a paper about why eyelashes are curly, which they describe as “silly enough to be Feedback material”. Rude: this is a deeply serious column about serious things.

The research is mostly about the physics of eyelashes, explaining how they transfer water away from our eyes so we can still see when it is raining. This process depends on “a hydrophobic curved flexible fiber array with surface micro-ratchet and macro-curvature”. There is a lot of stuff about adhesion forces and the importance of the curvature of the lashes for water drainage.

And then we get to the discussion section where, as Karmela drily notes, “the authors go into aesthetic advice”. You see, “modern beauty standards” encourage women to use mascara “to extend and fix eyelashes”, which “compromises the protective functions”. But fear not, the solution is at hand: “as a tip, for people with sparse eyelashes, hydrophobic curved false eyelashes could offer a practical solution for enhancing appearance while preserving eye protection.” Could a patent possibly be pending?

Feedback wonders whether the authors have any advice for middle-aged writers whose eyebrows grow too long, causing them to look like a macaroni penguin unless regularly trimmed. For a friend.

Worst to-be-read pile ever

Feedback has somehow got onto the mailing list for Spines, a tech company aiming to disrupt the publishing industry through the power of artificial intelligence.

By using AI to do the editing and other jobs previously done by skilled and salaried humans, Spines aims to publish 8000 books in 2025. To which Feedback says, yes please. When one looks at the structural problems in the publishing industry, such as the dire fact-checking standards in non-fiction output, one can only conclude that what we really need is a deluge of even more books of an even lower quality.

Got a story for Feedback?

You can send stories to Feedback by email at feedback@newscientist.com. Please include your home address. This week’s and past Feedbacks can be seen on our website.

Leave a Comment