A new report from the OECD (Global Debt Report 2024: Bond markets in a high debt environment) provides some interesting — if concerning — evidence of the continued vulnerability of far too many developing countries to the whims of bond investors. The report is mainly concerned with OECD countries, but the data it provides for emerging and developing countries points to some serious potential problems in the near future.

The dramatic expansion of global bond markets (for both sovereign and corporate bonds) in the recent past is now well-known. The total value of these bonds, at around $100 trillion, makes them almost as large as the estimated total global GDP.

OECD governments account for more than half of this, with the share of the US rising rapidly to more than a quarter of total bond values in 2023. But the rise in gross bonds issued by emerging and developing economies (hereafter EMDEs, using the World Bank’s classification) is also very striking.

Sharp increase

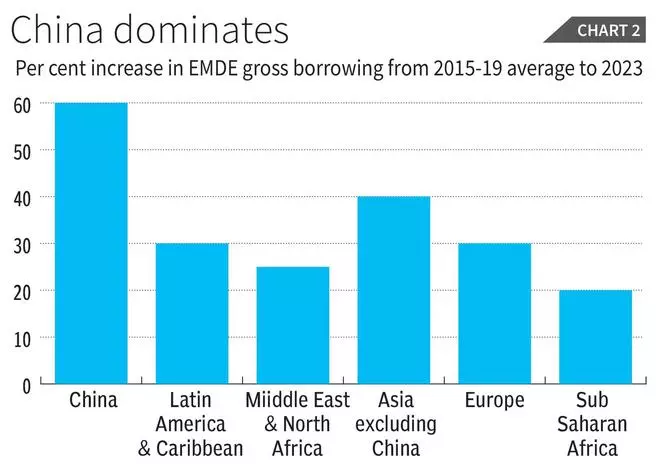

Chart 1 shows the significant increase in annual gross bond borrowing by EMDEs since 2007. The earlier peak of $2.7 trillion in 2011 was surpassed in pandemic year 2020, but since then bond borrowing has grown even more sharply to reach $3.9 trillion by 2023. This increase in bond issues by EMDEs was dominated by China, as Chart 2 suggests, with data using 2015-19 averages as base.

Indeed, public bonds issued in China in 2023 more than doubled over the previous year (bringing China’s share of gross borrowing to 37 per cent) because of increased public spending designed to revive growth.

The growing indebtedness of (mainly provincial) governments in China has been a focus of much discussion, but it is important to remember that almost all of China’s public debt is denominated in its own currency, renminbi, and so it is relatively protected from the shifts in cross-border capital flows and changes in interest rates that buffet other EMDEs. Similarly, the ratio of new bond issued in foreign currency by other Asian governments was only 2 per cent.

Meanwhile, the relatively lower increase in borrowing in Sub-Saharan Africa indicates that the region is once again facing difficulties accessing global bond markets in recent years; in fact, bond issuance in foreign currencies in this region fell from 5 per cent in 2022 to 1 per cent in 2023. In the MENA region, gross borrowing actually declined by 10 per cent between 2022 and 2023.

However, this more modest borrowing or focus on domestic borrowing only does not mean that the debt difficulties of several EMDEs have reduced very much.

Repayment difficulties

The legacy debt continues to play a major role in creating repayment difficulties, especially because much of it was taken on in the period when access to foreign currency borrowing was much easier for almost all EMDEs.

This is an important issue because quite a lot of such sovereign bonds are due to mature in the next three years, as is evident from Chart 3. For both Latin America and the Caribbean and the MENA regions, more than 40 per cent of such debt falls due within three years.

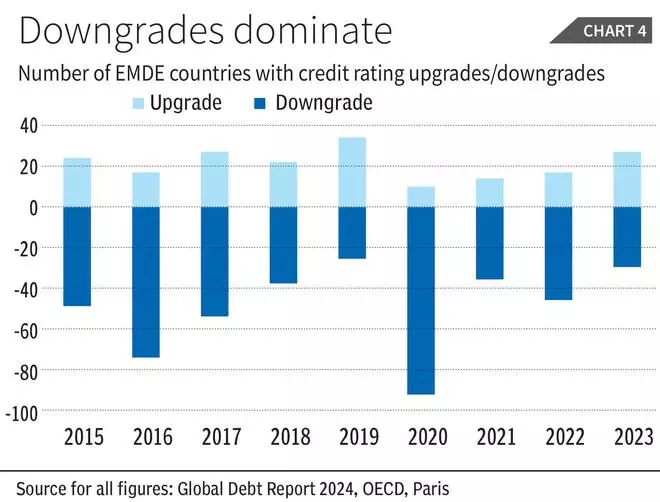

Meanwhile, credit rating agencies are not helping, with the number of countries experiencing downgrades almost always significantly greater than those receiving upgrades.

As Chart 4 shows, the worst year was 2020 when 91 countries experienced downgrades, but the relatively few numbers of upgrades throughout the period since 2015 indicates how difficult it has become to improve credit rating that has been downgraded.

Most of the downgrades have occurred in low and lower middle income countries.

The greater “stringency” of bond markets to EMDE debt is also indicated by the average term-to-maturity (ATM) which increases when debtors are perceived more favourably. For the average of all EMDEs, the ATMs of sovereign bonds issued in 2023 increased to 4.8 years, compared to 4.4 the year before.

In low-income countries, it surprisingly increased from 5.4 in 2022 to 5.9 in 2023, but this is misleading, because although it actually declined for all countries in this group except Tanzania and Uganda.

In general, the lower ATMs represent a higher share of short-term borrowing, which makes countries particularly vulnerable to refinancing risks in a context of globally worsening credit outlooks.

Another concern is the average spread of EMDEs’ sovereign bond yields over the benchmark 10-year US Treasury yield. There was a slight decrease on average in 2023 compared to 2022, but the average yield is still above 1,000 basis points (10 per cent) in Sub-Saharan Africa. This makes such borrowing so expensive as to be prohibitive, and has emerged as not just a symptom but even a leading cause of debt distress.

Refinancing risk

Since so many bonds will mature by 2026, this makes the refinancing risk for such countries particularly great.

Refinancing risk is also large for countries in other regions such as Moldova (with more than 60 per cent of marketable debt, equal to 8 per cent of GDP maturing in 2024) and Argentina (45 per cent of marketable debt, or 10 per cent of GDP).

As bond markets become even more volatile with growing unpredictability of policies especially in the advanced economies, particularly the US, the dangers of excessive exposure to these markets are particularly clear. It is clearly time for the developing world to consider a new pattern of financing development.

Leave a Comment