Low doses of a drug used to treat ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) could help people focus on the road when driving for long, monotonous stretches risks sending their mind wandering.

Researchers from Australia’s Swinburne University were curious about risks and benefits the pharmaceutical methylphenidate might have on driving performance, specifically in cases of individuals who don’t have ADHD.

Up to 90 percent of people medicated for their ADHD are prescribed the drug, which is commonly sold under the brand name Ritalin. For a medicated person with ADHD, driving without it can feel a bit like driving without their glasses.

Adults with ADHD are more at risk for road accidents, motor vehicle injuries, traffic tickets, and hard braking events. Taking methylphenidate is known to improve their driving performance. All this probably contributes to the fact that ADHD medication can literally add years to some people’s lives.

Yet many individuals take methylphenidate without a prescription. In the US alone, 5 million adults misuse prescription stimulants by taking them at higher doses, longer durations, or simply without a script. It’s important to know how these people may be affected while driving under the influence of unauthorized stimulants, especially those tasked with long and monotonous journeys.

This study enlisted 25 mentally and physically healthy drivers without a diagnosis of ADHD to learn what impact methylphenidate might have on their driving performance.

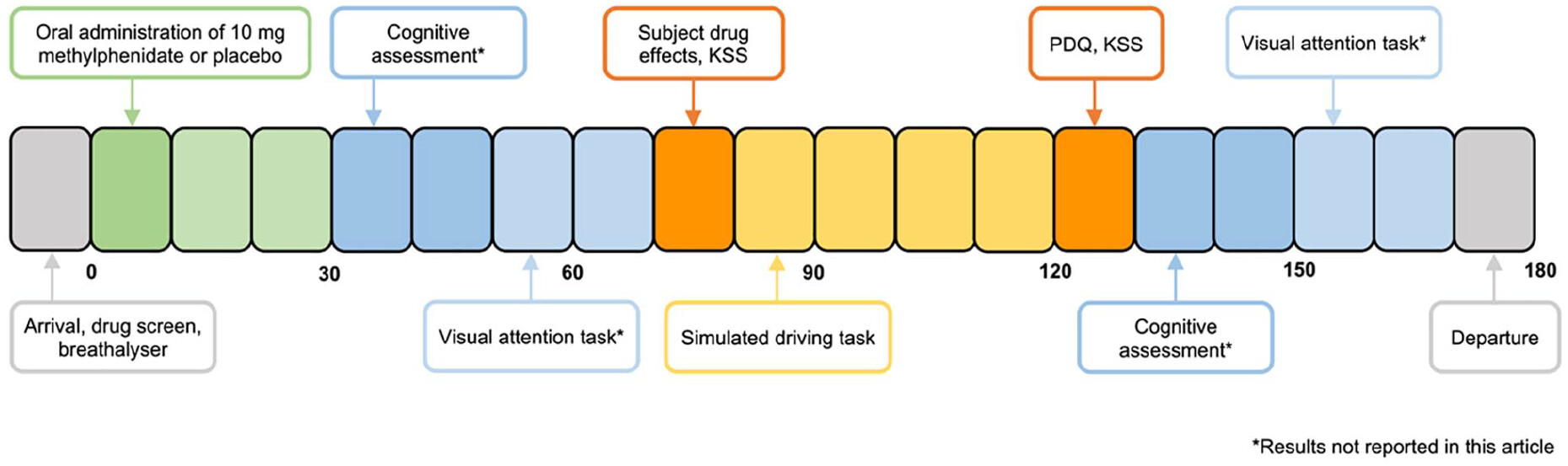

The volunteers were given 10 mg of methylphenidate or a placebo 85 minutes before stepping behind the wheel of a driving simulator that mimics a 105-kilometer (65-mile) bi-directional, four-lane highway with standard Australian road markings and signage. The experiment was undertaken twice, with different participants allocated the placebo and drug.

They were asked to ‘drive’ for 40 minutes, maintaining a steady 100 kilometers per hour speed in the left-most lane. Occasionally, traffic conditions required them to overtake other vehicles.

While the participants focused on the ‘road’, a machine kept close watch on their eye movements, tracking eye fixation duration and rate via a driver-facing camera mounted on the dashboard, and the computer recorded how far the drivers deviated from the center of their lane.

A mathematical algorithm assessed how dispersed or focused the drivers’ gazes were during the task, as well as how random or structured their visual scanning behaviour was.

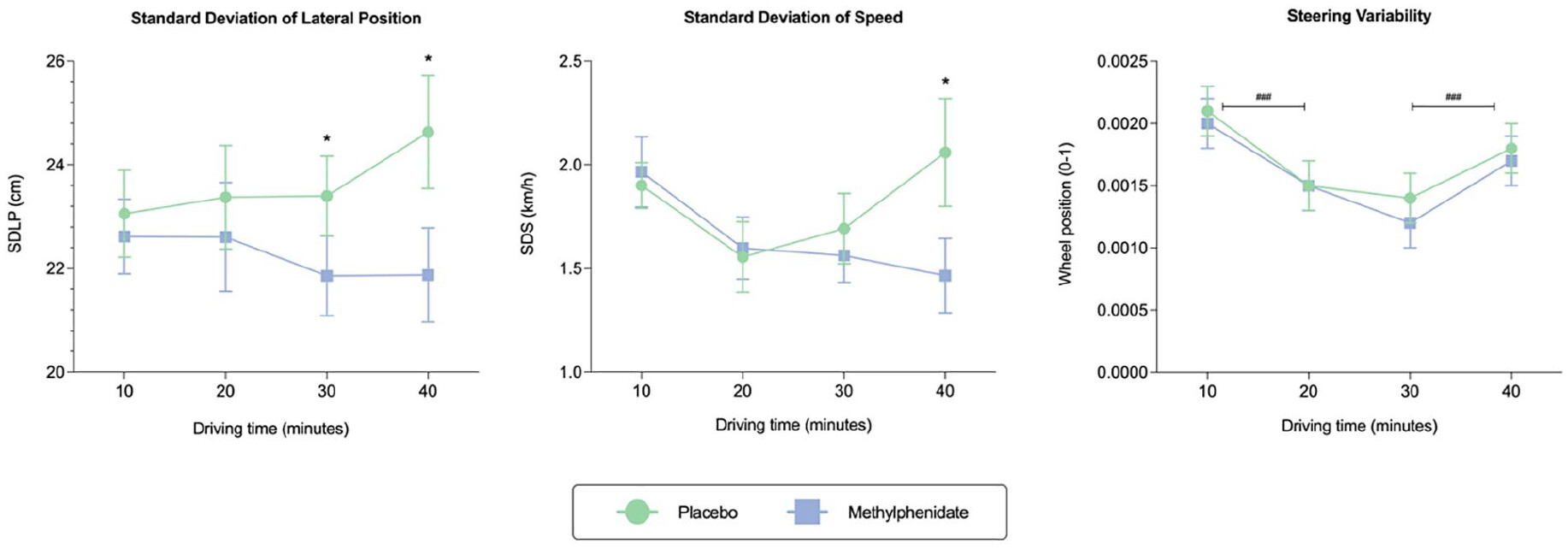

“Methylphenidate significantly improved driving performance by reducing lane weaving and speed variation, particularly in the latter half of the drive,” the authors report.

“Although a significant reduction in fixation duration was observed, all other ocular metrics remained unchanged.”

Methylphenidate reduced the drop in performance drivers usually experience during driving tasks, and in comparison to the placebo, drivers who took the drug had better vehicle control and maintained a more constant speed.

It didn’t cause any problems with people’s visual scanning, although it didn’t seem to improve it, either.

Previous studies raised concerns about a ‘tunnel vision’ effect associated with psychostimulants that could limit a driver’s ability to respond to sudden or unexpected obstacles entering from the periphery, like a pedestrian or car.

While this effect didn’t show up in the latest study, the authors suggest it may be because they used a relatively low dose taken short-term.

This study doesn’t capture the effects that might be seen at higher doses or taken for longer, which, they write, “are arguably more common in real-world misuse scenarios and likely associated with road traffic collisions.”

“There is a clear need for further research in this area, particularly studies aimed at identifying more pronounced alterations in ocular behaviour caused by methylphenidate and other psychostimulants,” the authors conclude.

The research was published in Journal of Psychopharmacology.

Leave a Comment