The famous helmet from the ship burial at Sutton Hoo in England may be evidence that Anglo-Saxon warriors fought as mercenaries for the Byzantine Empire in the sixth century, a new study finds.

The helmet and chain mail coat found near it have distinctive features that indicate they were copies of Byzantine armor, study author Helen Gittos, a medieval historian at the University of Oxford, told Live Science.

These martial artifacts, in turn, suggested that the man interred in the ship burial at Sutton Hoo — possibly the early Anglo-Saxon king Raedwald — had brought back Byzantine armor after fighting in what was then the Far East; the armor is made in a distinctive Anglo-Saxon style, and Gittos speculates the warrior had later asked English workers to make an ornate copy, which he was eventually buried with.

Gittos said the chain mail coat from Sutton Hoo is now badly rusted, but it seemed to have been modeled after chain mail worn by some soldiers in the Byzantine army at that time. The gold- and jewel-encrusted Sutton Hoo helmet, too, may not look very Roman at first glance, but it has articulated cheek guards and a neck guard, which were distinctive features of Roman helmets, she said.

In the new study, published Jan. 2 in the journal The English Historical Review, Gittos argues that some of the artifacts from early English graves and settlements suggest some Anglo-Saxon warriors fought for the Byzantine Empire against the Sasanian Persians — contrary to earlier suggestions that these objects had been acquired through trade.

Related: Anglo-Saxon teen girl discovered buried with lavish jewelry strewn across her head and chest

Early Anglo-Saxon warriors

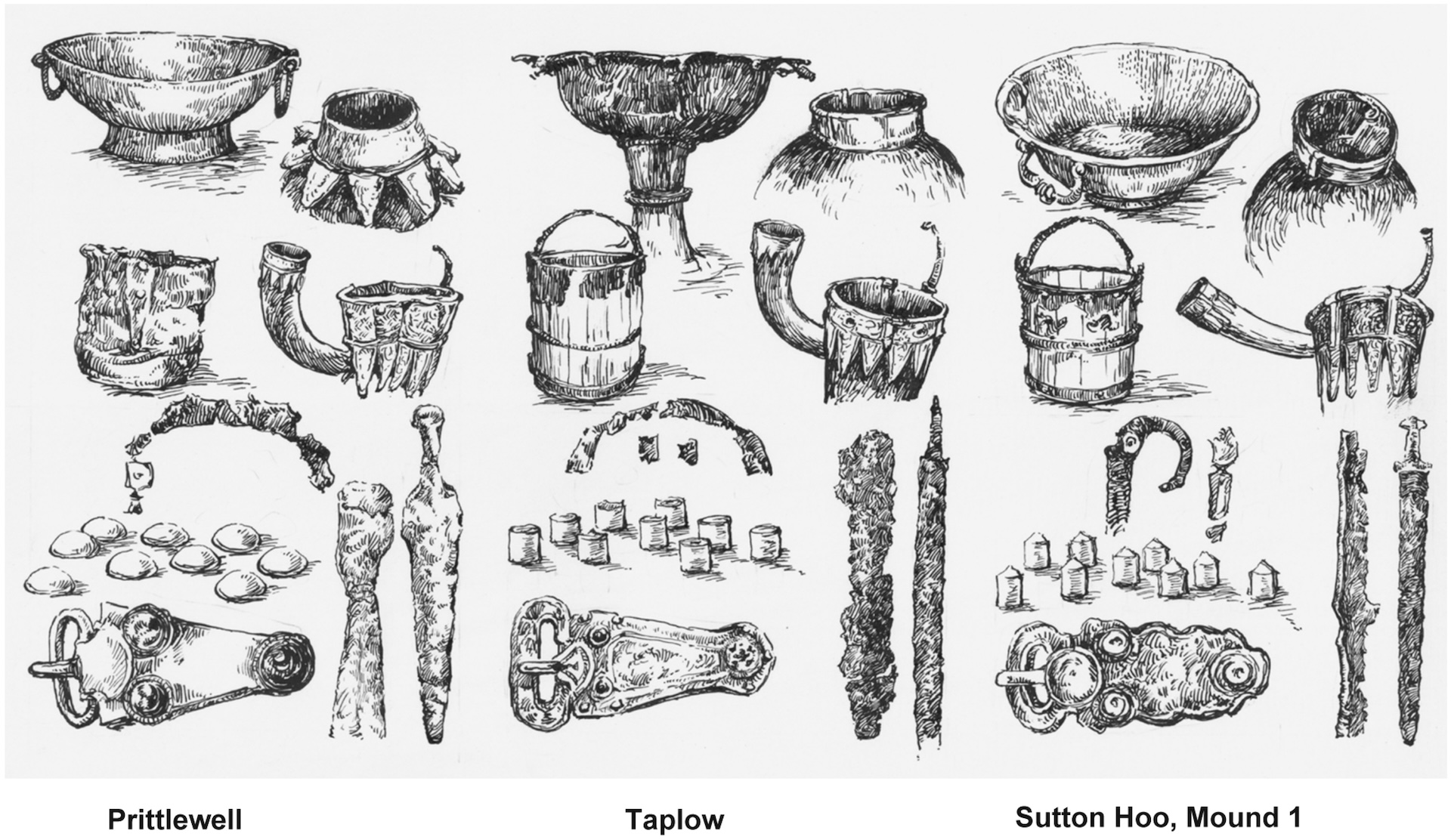

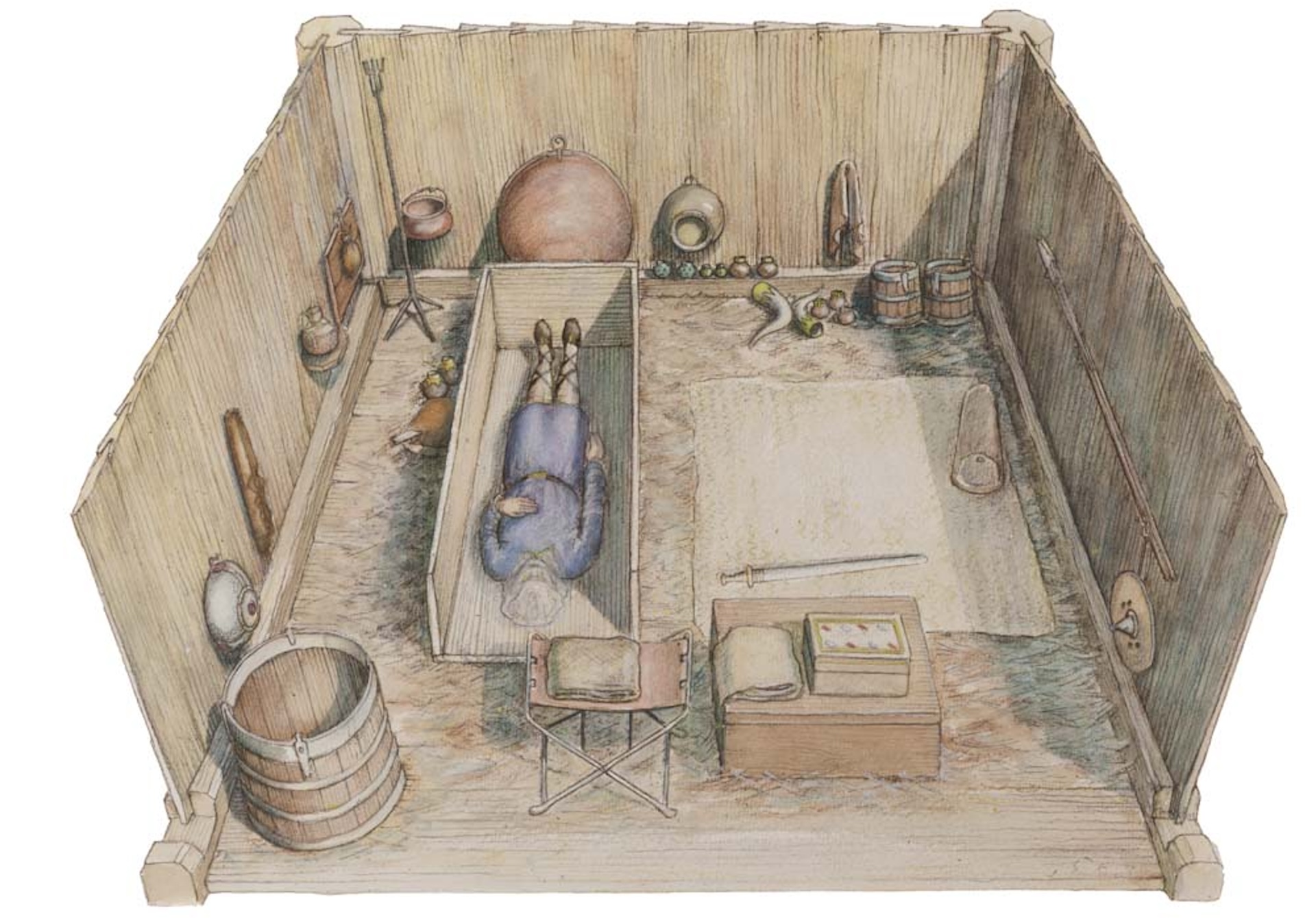

The Sutton Hoo site, which includes the ship burial and more than a dozen other graves, was discovered in 1939, just before the start of World War II. While Sutton Hoo yielded many artifacts, it wasn’t until the 2003 discovery of the “Prittlewell Prince,” an Anglo-Saxon nobleman buried in the Essex region east of London, that many of the Sutton Hoo findings and other Anglo-Saxon artifacts were better understood, Gittos said. Unlike the Sutton Hoo graves, the Prittlewell grave had never been looted by grave robbers, and it was excavated with modern techniques, resulting in a precise date between 580 and 605.

Among other artifacts, the Prittlewell grave contained a bronze pitcher, silver spoons and metal bowls that appear to have been made in the eastern Mediterranean but were not valuable enough to have been traded, Gittos said. Instead, she argued, it seemed likely that the early Anglo-Saxon nobleman buried in the Prittlewell grave had acquired them when he was fighting in the Far East.

Artifacts from other early English graves also suggest such contacts with the Byzantines, she said, many centuries before some Anglo-Saxons fought as bodyguards in the Byzantine Varangian Guard.

“Those who returned brought back with them metalwork and other items which were current, and distinctive, and not the kinds of things that were part of normal trading networks,” Gittos wrote in the study.

Against the Sasanians

Gittos noted that the Byzantine leaders launched a major military campaign in the 570s against the Sasanian Persians who threatened their Eastern territories, and historical records show the Byzantine leaders recruited mercenary fighters from “both sides of the Alps.”

The promised pay “rendered the recruits’ hearts eager for danger through a flowing distribution of gold, purchasing from them enthusiasm for death by respect for payment,” according to a seventh-century Byzantine historian.

Foreign warriors recruited by the Byzantine Empire were initially given a suit of armor and then money to buy more armor, weapons and equipment. Elaborately decorated horse equipment, depictions of horses on other artifacts and even the skeletons of horses, have also been found in the graves of early Anglo-Saxon warriors, which suggests their skill as horsemen was especially valuable. “These were experienced cavalry worth recruiting,” Gittos wrote in the study.

King’s College London historian and archaeologist Ken Dark, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science it was a “fascinating interpretation.”

It had been suggested before that some of the artifacts from Anglo-Saxon settlements and graves may have originated in the Byzantine world.

“Nevertheless, there is no direct evidence that western Britons fought in Byzantine armies, although their military prowess — especially at fighting in woods — is noted in the Emperor Maurice’s [sixth-century war manual] Strategikon, so this might be possible,” Dark said in an email.

Leave a Comment