Exercise is a topic that’s muddied with mainstream misconceptions. Here are five common exercise myths, debunked by science.

Myth: Muscle soreness is caused by lactic acid.

Glycolysis is a reaction within the cell where a molecule of glucose, or sugar, is broken down into smaller molecules to release energy, ultimately producing lactic acid as a side product.

Accumulation of lactic acid slightly lowers the pH inside the cell, which messes up some steps of the glycolysis reaction, reducing the energy output of the process. The muscle can no longer get enough energy from glycolysis to maintain its contraction, and as muscle fatigue sets in, is forced to relax. To allow the muscle to keep exercising, the lactic acid is immediately secreted from the muscles as a waste product and cleared away by the bloodstream within seconds. This means that lactic acid does not linger around the muscles long enough to make them sore after exercise.

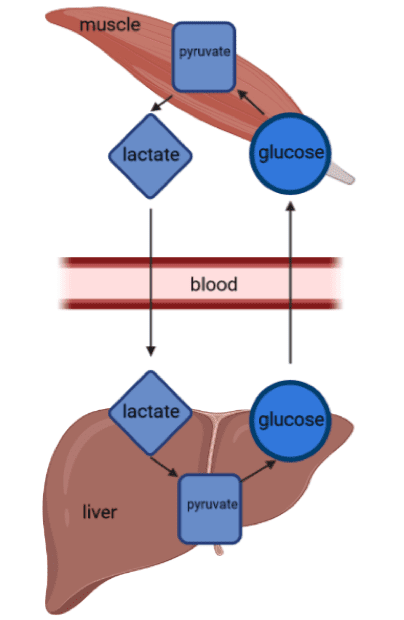

Glycolysis in the muscle produces lactate (lactic acid), which is carried away by the blood to be recycled back into glucose in the liver. This is called the Cori cycle.

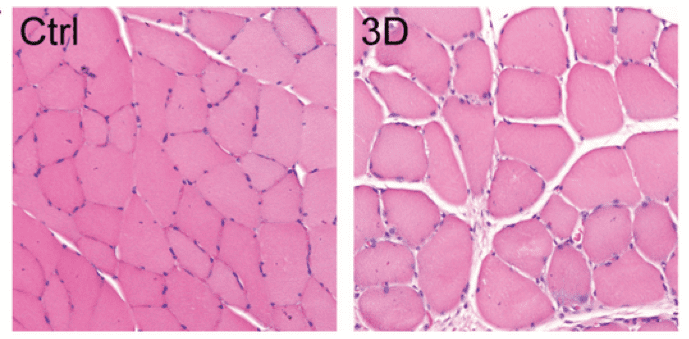

So, what causes muscle soreness? It’s a subject that’s still being investigated, but right now the leading theory is that strenuous exercise inflicts mechanical damage to the structure of muscle cells. Cellular damage results in inflammation and a sensation of pain that goes away over time as the muscle heals. The most effective way to manage muscle soreness is the same as most other mechanical injuries: rest, cold compress, and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Myth: Losing muscle mass after not working out for a while sets you back to square one.

The human body is incredibly dynamic. It undergoes a wide variety of biological adaptations, some that take place within the cell and some that involve the entire body, in response to exercise. One of the most visible is muscular hypertrophy, an enlargement of muscle fibers to bear more weight. Hypertrophy is caused by an increase in the amount of proteins that help muscles contract and is one of the more temporary adaptations that tends to revert to baseline without regular training. Seeing this loss happen can be disheartening, but there are some exercise-induced changes that tend to stay around longer, and help your bulging biceps return faster, too.

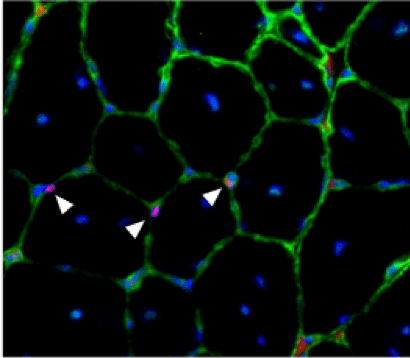

One muscular adaptation to exercise is satellite cell fusion to damaged muscle fibers. Satellite cells are small muscle stem cells that hang out between larger mature muscle fibers. The damage to muscle cells from exercise activates satellite cells to fuse with the fiber, healing it. This means that the nucleus (the part of the cell where DNA is stored) of the satellite cell is permanently added to the many nuclei of the muscle fiber cells. DNA serves as the instructions that cells use to produce proteins, like those that make muscles contract and enlarge with training. The result is that a muscle fiber with more nuclei can produce these proteins faster to get stronger. Even though the proteins that make muscles big will degrade over time with no training, those nuclei stick around for life. So, the second time you work out after building muscle mass and then losing it, that mass comes back quicker than the first time.

Muscles aren’t the only body part that improve with exercise; the nervous system is honed with training too. Muscle contraction doesn’t happen on its own — it must be stimulated by messages from spinal nerves first. Resistance exercise, like lifting weights and bodyweight exercises like planks, trains these nerves to fire faster and stronger to tell more muscle fibers to contract harder. This ultimately results in a quicker and more powerful exertion of force, and is a big part of increasing strength with exercise. Even after muscle mass diminishes when training stops, these neural adaptations tend to persist longer, and the muscle is still stronger than it was before training.

Myth: Exercising a certain muscle group reduces the fat mass surrounding that body part.

This notion is called spot training or spot reduction, and is misleading in regards to how body metabolism functions.

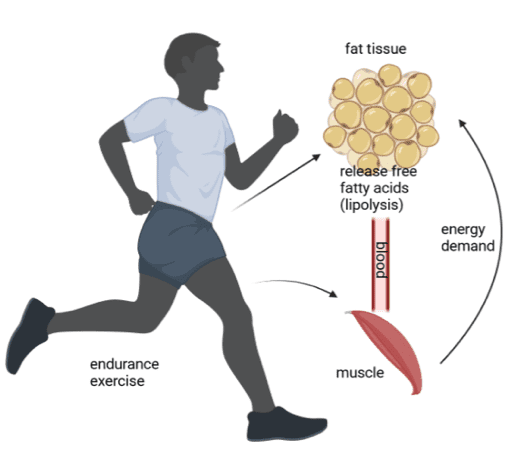

Exercises like push-ups, sit-ups, and other high-intensity, short-duration activities mainly utilize carbohydrates as fuel to sustain those sudden bursts of activity. Fat molecules called lipids, which are stored in the body’s fat depots, are broken down in a type of chemical reaction called oxidation. Fat-burning oxidation is more important for fueling long-duration cardio exercise, like running and swimming. That means that the type of exercise that reduces body fat is pretty different from the type of exercise that builds strength.

Furthermore, lipids that are secreted from fat cells don’t simply travel directly into the nearest muscle cells. They are released into the bloodstream as molecules called free fatty acids, and are carried all throughout the body to whichever muscle groups are in need of fuel for energy. So doing crunches every day, while good for your health, won’t eliminate belly fat by itself.

Myth: Sweating a lot means you’re burning a lot of calories.

Sweat is important for regulating body temperature, especially during exercise, when the active muscles are generating heat. Generally speaking, more intense physical activity results in more sweating because of the body’s greater need to get rid of the heat produced by its muscles. But sweat is by no means a direct measure of energy expenditure, nor does the body “sweat out” calories, fat, or toxins through the glands on the skin (it’s just water and salt). There is also no evidence that exercising in the heat enhances calorie burning efficiency, and requires caution because of the resulting dehydration and risk of overheating.

Myth: The greatest benefit of exercise is weight loss.

Many people embark on exercise regimens in hopes of slimming down, but misleading conventional wisdom has conflated body fat content with overall health. While these factors are related, some of the most important benefits of exercise can be conferred independently of weight loss.

The two main types of fat tissue in humans are visceral fat — the kind that surrounds the body’s organs — and subcutaneous fat, the more innocuous jiggly kind. Regular exercise can trim down both types, and reducing visceral fat mass does significantly alleviate the risk of serious health complications like cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type II diabetes. However, individuals who engage in regular exercise experience lower rates of CVD deaths and decreased risk of type II diabetes than sedentary individuals, regardless of body fat mass. In fact, the CDC lists physical inactivity and being overweight as separate risk factors for development of type II diabetes.

Resistance training, which has less of an impact on weight loss, still offers long-term health benefits. Muscular strength is a reliable independent predictor of mortality, indicating a crucial role in preventing the development of physical disabilities and chronic illnesses like CVD and kidney disease. Additionally, muscular strength is positively associated with both physical and mental quality of life in the elderly, promoting functional independence and minimizing chronic pain.

Despite the mainstream emphasis on weight loss, many of the most important health benefits of exercise don’t depend on a reduction in body fat. So even if you’re not seeing visible results with your exercise regimen, you are still taking good care of your health.

The post Five Myths About Exercise appeared first on Illinois Science Council.

Leave a Comment