Humans today are living longer than ever before, but how many of those added years are spent in good health?

A data-crunching survey covering 183 member nations of the World Health Organization has now confirmed what some scientists feared: while years are being added to most people’s lives, healthy life is not being added to most people’s years.

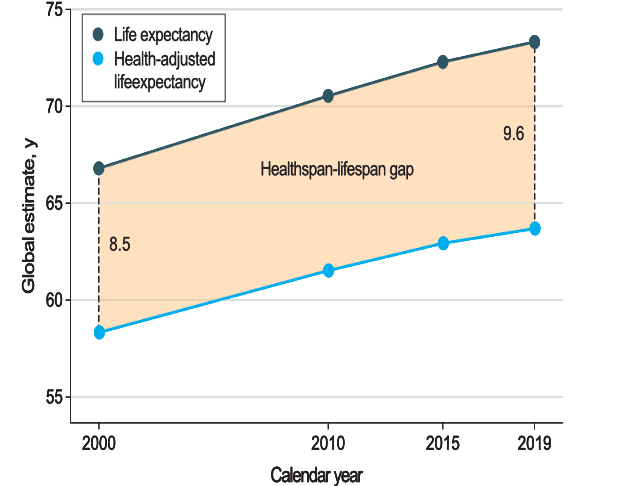

Researchers at the Mayo Clinic found that people around the world in 2019 were living 9.6 years of life burdened by disability or disease – an increase of 13 percent from 2000.

In that same time frame, global life expectancy has increased 6.5 years, and yet health-adjusted life expectancy has only increased 5.4 years.

In the US, the gap between lifespan and ‘healthspan’ is growing particularly wide.

Between 2000 and 2019, life expectancy in the US increased from 79.2 to 80.7 years for women, and from 74.1 to 76.3 years for men.

When adjusting for healthy years of added life, however, the span only increased by 0.6 years among men. And among women, while health-adjusted life expectancy fluctuated slightly over time, in 2019 it matched the figure seen in 2000.

The expanding gap means if an American woman lived to the expected 80.7 years of age, the last 12.4 years of her life would on average be impacted by disease or disability.

According to public health researchers Armin Garmany and Andre Terzic, the healthspan-lifespan gap in the US is 29 percent higher than the global average.

“The data show that gains in longevity are not matched with equivalent advances in healthy longevity. Growing older often means more years of life burdened with disease,” says Terzic, a cardiovascular health researcher at the Mayo Clinic.

“This research has important practice and policy implications by bringing attention to a growing threat to the quality of longevity and the need to close the healthspan-lifespan gap.”

The results align with previous studies from around the world, which typically consider one nation at a time, and which suggest that while women tend to live longer than men, they also accrue more unhealthy years of life, mostly from chronic health conditions.

In light of these trends, the WHO recently introduced a new metric known as health life expectancy (HALE) to try and measure the burden of disease and disability in older age, especially after 60.

In 2020, WHO and the United Nations declared a 10-year global plan of action. In 2022, officials wrote that to “ensure older persons are not left behind, there is a pressing need to strengthen measurement and address the data gaps.”

Researchers at the Mayo Clinic have now responded to that call.

In a review of the last two decades, Garmany and Terzic have highlighted “a chasm between advances made in longevity, a traditional measure of life expectancy, and healthy longevity, a contemporary indicator of quantity and quality of life.”

The widening gap between these two measures is now confirmed as a global trend, and while this is a universal problem, it will need to be addressed in a multifaceted way, from country to country, and between different groups of people.

For instance, the gap in lifespan-healthspan is particularly pronounced among the female sex, who tend to carry a greater burden of noncommunicable diseases, like musculoskeletal, genitourinary, and neurological diseases later in life.

The largest healthspan-lifespan gaps were observed in the US (12.4 years), Australia (12.1 years), New Zealand (11.8 years), the UK (11.3 years), and Norway (11.2 years).

Meanwhile, the smallest gaps were seen in Lesotho (6.5 years), the Central African Republic (6.7 years), Somalia (6.8 years), Kiribati (6.8 years), and Micronesia (7.0 years).

Given that poor health was analyzed using a blanket measurement of disease and disability, researchers say the next step is to dig further, figure out which groups of people are suffering the most in their later years, and how we can best help them age with dignity.

“The widening healthspan-lifespan gap is a global trend, as documented herein, and points to the need for an accelerated pivot to proactive wellness-centric care systems,” the two authors conclude.

The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Leave a Comment