Scientists have discovered a new way emperor penguins detoxify mercury, revealing a surprising detoxification pathway not seen in animals before.

This finding, published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials, helps us understand how mercury is processed in wildlife and could aid in protecting ecosystems and tackling mercury poisoning.

Mercury is one of the most dangerous chemicals for public health, according to the World Health Organization.

It builds up in animals over time and becomes more toxic as it moves up the food chain.

In aquatic environments, it turns into methylmercury, a highly neurotoxic substance.

Studying how animals deal with this toxin is crucial for wildlife protection and creating treatments for mercury exposure.

The research was led by Alain Manceau, a scientist at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in France, along with collaborators from the University of La Rochelle, the United States Geological Survey, and the University of California, Davis. Over the years, the team has studied how animals, especially top predators like seabirds and marine mammals, detoxify mercury.

In 2021, the team found that animals like giant petrels and pilot whales use selenium to detoxify methylmercury.

The mercury is converted into a harmless substance called mercury selenide, which has little toxic impact as long as enough selenium is available. But scientists wanted to know if animals lower in the food chain, like emperor penguins, use the same method.

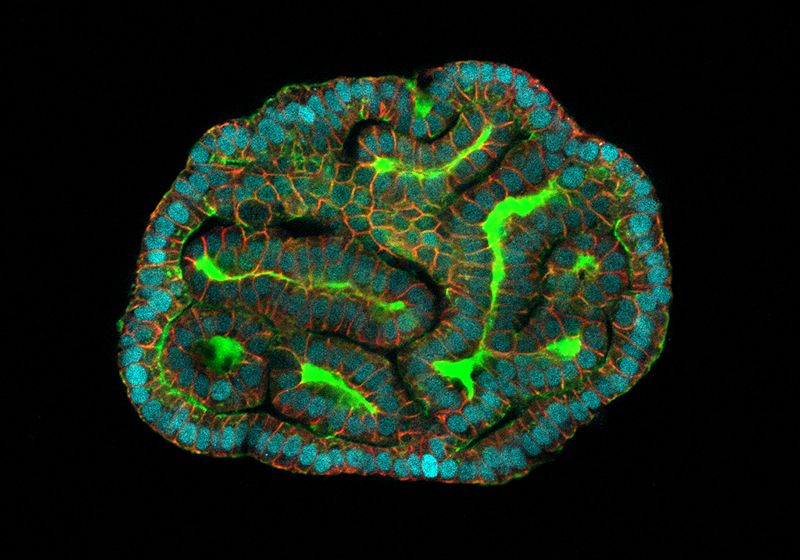

Emperor penguins, which mostly eat silverfish and squid, are exposed to less mercury than top predators. Using advanced X-ray techniques at the ESRF, scientists found that penguins do use the same selenium-based detoxification pathway as giant petrels, but with an important twist.

Penguins also use a second, simpler pathway to deal with mercury. In this method, toxic mercury binds to cysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, forming a compound called a Hg-dithiolate complex. This new pathway was previously observed only in bacteria, making this the first time it’s been found in animals.

“This discovery shows that lower-trophic animals like penguins, which have less mercury in their diet, rely on this simpler detoxification process because they don’t need the advanced system seen in predators like giant petrels,” Manceau explained.

The team also analyzed penguin eggs collected during an Antarctic expedition. They found that mother penguins transfer some mercury to their eggs, mainly in the albumen (egg white), which contains methylmercury. However, in the yolk, some mercury is detoxified using the selenium pathway. Despite this, most mercury in the egg remains toxic due to the larger amount of albumen compared to yolk.

Interestingly, the study noted that penguins eliminate much more mercury during their molting process, as it is expelled through feathers. This is similar to how humans partially get rid of mercury through hair. However, mercury can also be passed from mother to baby during pregnancy, which can affect the baby’s neurodevelopment.

This research is an important step in understanding how mercury cycles through ecosystems. The discovery of this simpler detoxification pathway in penguins sheds light on how different species handle toxins. It also raises new questions about whether other animals, such as snakes, crocodiles, and tuna, use similar processes.

“Understanding these mechanisms is vital for protecting wildlife and managing mercury pollution,” said Paco Bustamante, a professor at the University of La Rochelle.

This study not only expands our knowledge of penguins and mercury detoxification but also provides a valuable foundation for further research on the impact of mercury in the environment and its effect on different species.

Leave a Comment