Scientists have discovered how tiny defects in ultra-thin materials like graphene can stop their natural ripples, freezing them in place.

This discovery could help engineers design better flexible electronics, energy storage devices, and water filtration systems.

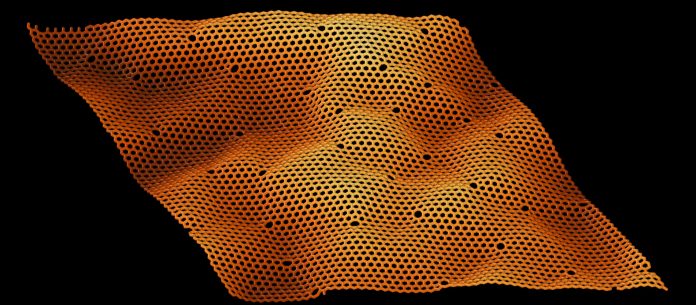

Graphene is a two-dimensional (2D) material that is just one atom thick. Though it may seem completely flat, at the atomic level, its surface naturally forms small ripples, like waves on a pond.

These ripples are important because they affect the material’s strength, electrical conductivity, and interactions with chemicals and fluids.

Understanding how defects influence these ripples could lead to major advancements in nanotechnology.

A team of international scientists, including researchers from the University of Cambridge, University College London, Imperial College London, and IBM, has investigated how these ripples behave when defects are introduced.

Their findings, published in PNAS, show that once a certain number of defects appear, the ripples stop moving, freezing the sheet in place.

Dr. Fabian Thiemann, who began this research during his Ph.D. and is now a scientist at IBM, explained that while experiments can capture the overall shape of ripples, they struggle to track their motion at the atomic level.

To solve this problem, the researchers used machine learning-based computer models to simulate how graphene and other 2D materials behave over time.

Using advanced simulations, the researchers observed how the ripples in graphene change depending on the number of defects. They found that:

- A perfectly smooth graphene sheet has natural ripples that move freely.

- A small number of defects slightly changes the movement of these ripples.

- When the number of defects reaches a certain level, the ripples freeze, making the sheet lose its flexibility.

Professor Angelos Michaelides from the University of Cambridge described the impact of these tiny defects as “remarkable,” highlighting the exciting possibilities for using this knowledge in nanofluidics, which studies how fluids move at a tiny scale.

Traditionally, defects in materials have been seen as flaws. However, this study shows that defects can actually be used to control the physical properties of 2D materials.

Dr. Camille Scalliet, now a researcher in Paris, explained that understanding how defects affect ripples can help engineers design materials with specific behaviors.

Professor Erich A. Müller from Imperial College London added that artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing materials science, allowing researchers to predict material properties more accurately and efficiently.

This could lead to the discovery of new materials with advanced functions.

The researchers are excited to continue their work, studying how graphene behaves when in contact with water or other materials.

According to Dr. Thiemann and Dr. Scalliet, “This is just the beginning of an exciting journey in materials science.” Their work opens the door to designing stronger, smarter, and more adaptable materials for the future.

Leave a Comment