Imagine you are looking to invest in a company. You feel it has a solid business model that you want to look further into the company before you invest. You labour for long hours poring over the company’s financial statements. You go on to build a detailed valuation model, and it turns out the stock is undervalued. You invest in the stock and wait for it to make money for you.

Now imagine you wake up one day to find out the company had fudged its accounts and see the stock price crashing. The very numbers that you believed were true have betrayed you. All your analyses and models are now worth less than the lint in your pocket. What if you had a crystal ball to foretell this? That’s Beneish M-score for you!

What it is

The M-score methodology was devised in a research paper by Messod D. Beneish, an accounting professor at Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. He profiled a sample of companies that had engaged in earnings manipulations and studied their distinguishing characteristics. He then arrived at an equation/ formula that establishes a relation between certain accounting ratios and the probability of earnings manipulation.

In the paper, Beneish found that the model identified nearly 50 per cent of the manipulating companies (from the sample) even prior to the public discovery of the manipulation and so, he suggests investors use the model as a screening device, before investing real money.

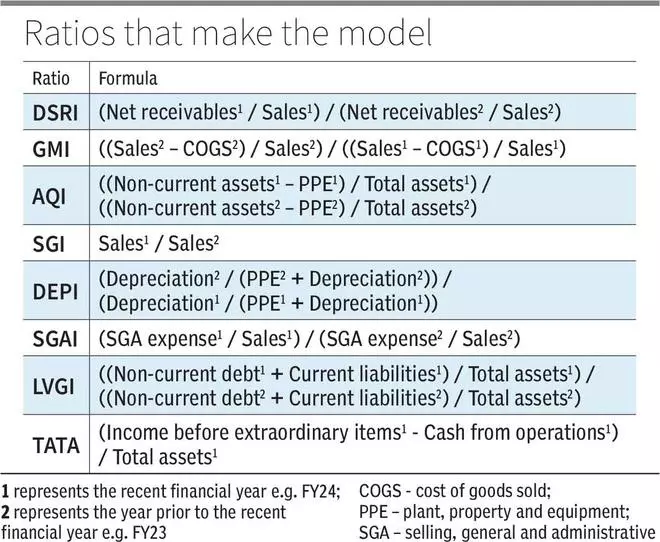

The model uses eight financial ratios weighed by their respective coefficients to identify whether a company has manipulated its profits. The M-score equation is as follows:

M-score = -4.84 + 0.92 DSRI + 0.528 GMI + 0.404 AQI + 0.892 SGI + 0.115 DEPI – 0.172 SGAI – 0.327 LVGI + 4.679 TATA

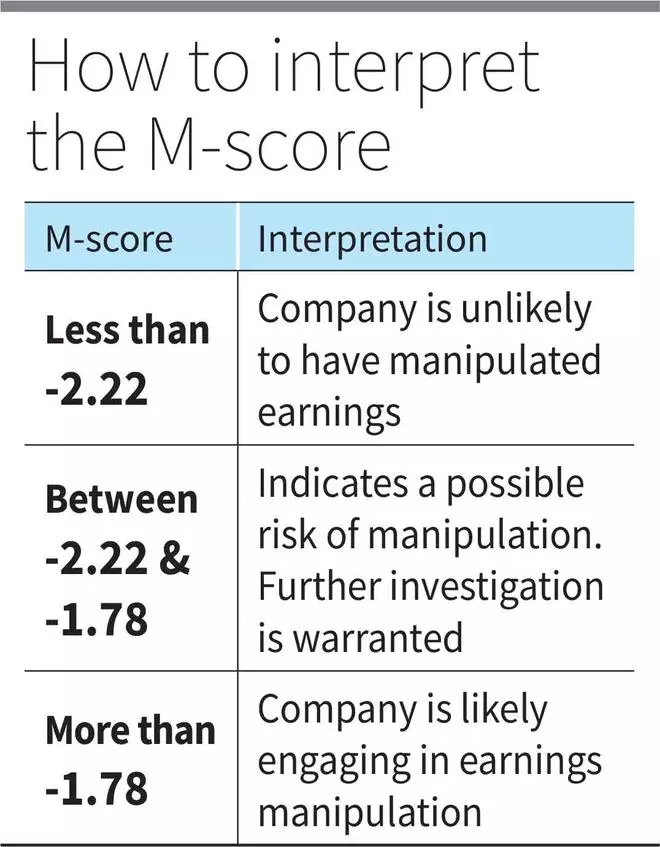

DSRI, GMI, AQI, etc are accounting ratios and are explained in detail later. The equation will give you a number and this is how it is to be interpreted.

The crystal ball

As mentioned, eight ratios make the M-score equation. Beneish found that the companies that manipulated earnings did either of the following to fudge books – accelerating revenue recognition, accruals not backed by realisations, cost deferrals and reducing depreciation, among others. Hence, you’ll find them to be underpinning the eight ratios.

The ratios and the formulae to work them are given in the infographic. Here’s what they mean and the logic behind them.

DSRI – It stands for Days Sales in Receivables Index. The net receivables to sales ratio shows how much of sales is still in receivables, and not in cash. Companies might go lax on credit policy to inflate sales figures or even book fictitious sales, delaying cash flow and affecting liquidity. A ratio over 1 suggests sales could be artificially boosted.

GMI – Gross Margin Index. When GMI is greater than 1, it implies that the gross margin has deteriorated, which indicates that the company could be pushing sales by compromising on margin.

AQI – Asset Quality Index. Companies that are really strapped for surplus, often capitalise costs that should be expensed. This neat trick is called cost deferrals. These often appear on the balance sheet under non-current assets. The ratio subtracts productive assets such as plant, property and equipment to identify potential cost deferrals. A ratio over 1 suggests an increase in cost deferrals.

SGI – Sales Growth Index. Companies experiencing rapid growth may face pressure from investors, analysts and the like to continue delivering strong performance. This pressure can lead to unethical accounting practices, including earnings manipulation. A high SGI may indicate that a company is under pressure to maintain its growth trajectory.

DEPI – Depreciation Index. This ratio compares the rate of depreciation charge of the current year to that of the preceding year. Depreciation is an area, where there are quite a lot of estimates involved, such as the estimate of an asset’s useful life. Companies could manipulate such estimates to bring down the depreciation charge, thereby propping up the accounting profit. A ratio over one indicates such manipulation.

SGAI – Sales, General, Administration expenses Index. Typically, rising sales lead to higher SGA expenses. If sales increase without a corresponding rise in SGA expenses, it may indicate manipulation. This ratio compares current and previous year SGA expenses to sales. A ratio over 1 suggests manipulation is unlikely, explaining the negative coefficient for SGAI.

LVGI – Leverage Index. Companies that struggle with cash flow, rely more on external funding and that increases leverage. A ratio over 1 suggests manipulation is unlikely, as higher debt indicates the company’s recognition of financial distress. Beneish sees this as a positive from manipulation standpoint, as more debt invites scrutiny from lenders, credit rating agencies, bond trustees and the like. Hence, LVGI has been given a negative coefficient. This could also explain why some manipulators choose equity over debt to raise funds.

TATA – Total Accruals to Total Assets. Accruals refer to the difference between a company’s accounting profit and cash profit, divided by total assets for comparison with other firms. The ability to convert accounting profits to cash profits reflects the true quality of earnings. That is why even in calculation of intrinsic value, future cash profits are discounted. This ratio, weighted at 4.679, is crucial.

Pros and cons

The Enron scandal unravelled in 2001, but it was correctly identified in 1998 as an earnings manipulator by students from Cornell University using M-score. Noticeably, 15 Wall Street analysts were still recommending buying Enron shares at that point in time.

However, the M-score, which is a probability-based model, is not perfect. It can generate false positives, identifying non-manipulative companies as potential manipulators and false negatives, missing actual manipulators. In his 1999 study, Beneish found his model flagging only 76 per cent of the manipulators.

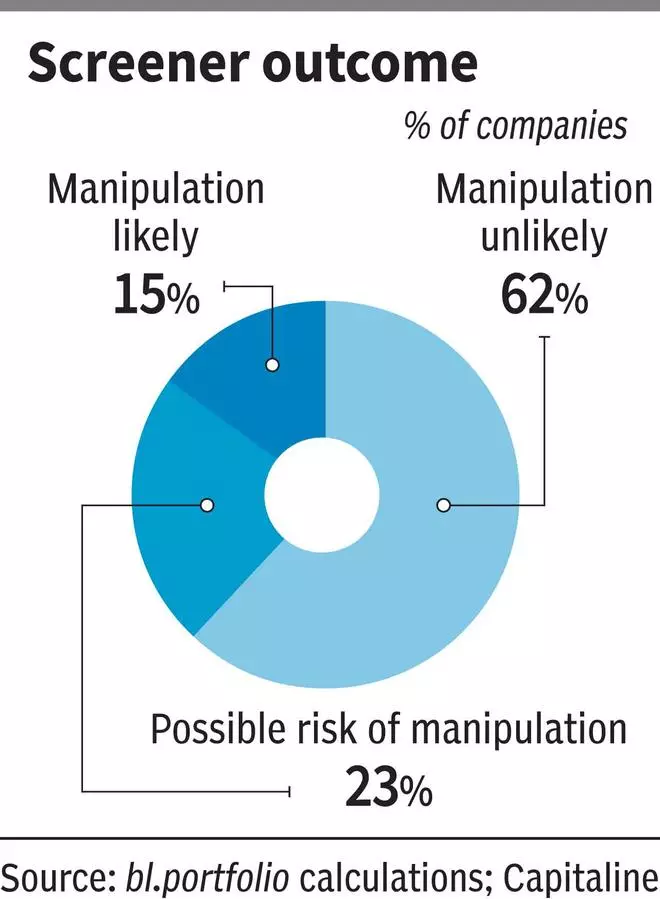

We ran a screener ourselves to check the model out. The universe had 357 NSE-listed stocks, filtered after removing BFSI companies from the top 500 companies by market-cap. The findings are as in the pie chart.

As said earlier, we did find a few false alarms. The model found cases such as sales growth boosted by genuine order-wins in the recent past as manipulations.

What could make the model an effective screener is applying it across multiple years to find if a company passes its test consistently. Also, even if the model flags a company to be fudging earnings, it is good to investigate why. Because bona-fide cases such as addition of a new product segment, a genuine re-estimation of useful life of assets could be flagged as manipulation.

In our future editions, we will write on other such established approaches to picking and screening stocks.

Leave a Comment