Carl Sagan famously said, “We are made of star-stuff,” but even he didn’t realize just how far that star stuff traveled before it got to us.

New Hubble data has shown at least some of the carbon that now makes up our bodies may once have drifted hundreds of thousands of light-years out of the galaxy and back.

Elements heavier than helium are forged in the hearts of stars, eventually released into the cosmos when those stars explode as supernovae. These ingredients are then fed into the next generation of stars and planets.

But it turns out those elements can take a major detour on the way. A new study shows that carbon ventures out of the galaxy itself, into a huge cloud of surrounding gas called the circumgalactic medium (CGM), before returning.

“The implications for galaxy evolution, and for the nature of the reservoir of carbon available to galaxies for forming new stars, are exciting,” says astronomer Jessica Werk, from the University of Washington.

“The same carbon in our bodies most likely spent a significant amount of time outside of the galaxy!”

The team used Hubble data to analyze the CGM of 11 star-forming galaxies, finding strong signals of carbon as far as 391,000 light-years away from the galaxy. For reference, the Milky Way’s visible disk is about 100,000 light-years wide.

“Think of the circumgalactic medium as a giant train station: It is constantly pushing material out and pulling it back in,” says University of Washington astronomer Samantha Garza, lead author of the study.

“The heavy elements that stars make get pushed out of their host galaxy and into the circumgalactic medium through their explosive supernovae deaths, where they can eventually get pulled back in and continue the cycle of star and planet formation.”

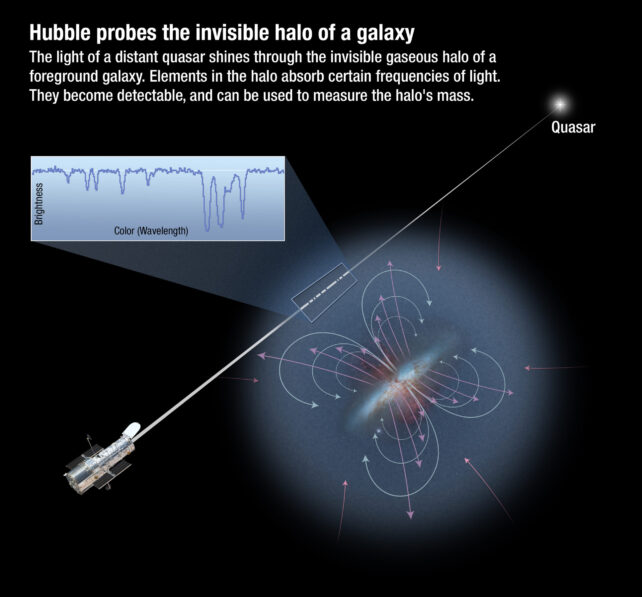

Every element interacts with light in a unique way, absorbing certain wavelengths, or colors, over others. Analyzing this spectrum can reveal which elements are present in a distant patch of space.

That’s how the team found this wandering carbon, using Hubble’s Cosmic Origins Spectrograph and nine distant quasars as the light sources. The researchers detected the fingerprint of carbon in the CGM of the target galaxies, estimating a minimum mass of about 3 million Suns out there.

It was previously known that the CGM cycles other materials out and back into galaxies, including hot, ionized oxygen, but the team says this is the first observation of cooler elements like carbon getting swept up in the motion.

Not every galaxy is home to these colossal conveyor belts, either. Galaxies that are actively forming new stars were churning through far more carbon than “passive” galaxies. Intriguingly, this also lines up with previous observations that showed that the CGM of star-forming galaxies had more oxygen cycling through.

“We can now confirm that the circumgalactic medium acts like a giant reservoir for both carbon and oxygen,” says Garza. “And, at least in star-forming galaxies, we suggest that this material then falls back onto the galaxy to continue the recycling process.”

Since the Milky Way is still forming stars, a percentage of the carbon and oxygen all around us has probably embarked on this intergalactic odyssey at least once.

Studying these galactic cycles could allow astronomers to better understand how and why galaxies start and stop periods of star formation. CGM dynamics can also reveal what happens when galaxies merge – a fate our own Milky Way is heading for. In fact, if you consider the invisible bubble of extra material in the CGM, it may already be underway.

If nothing else, it makes Sagan’s words even more poignant. The ‘star stuff’ inside us didn’t settle down straight away: it spent its youth on an incredible around-the-galaxy trip, before returning home and forming Earth, plants, and us.

The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Leave a Comment