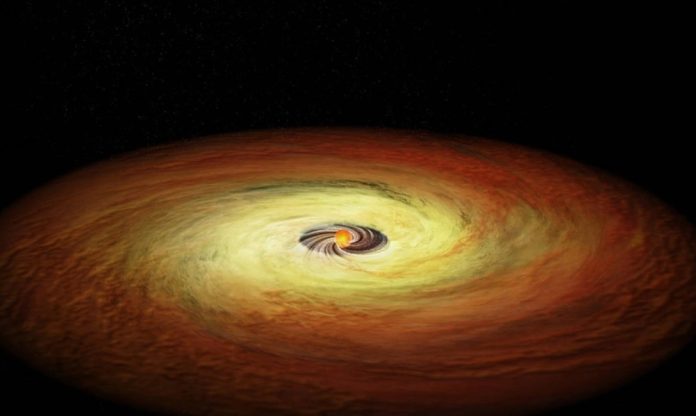

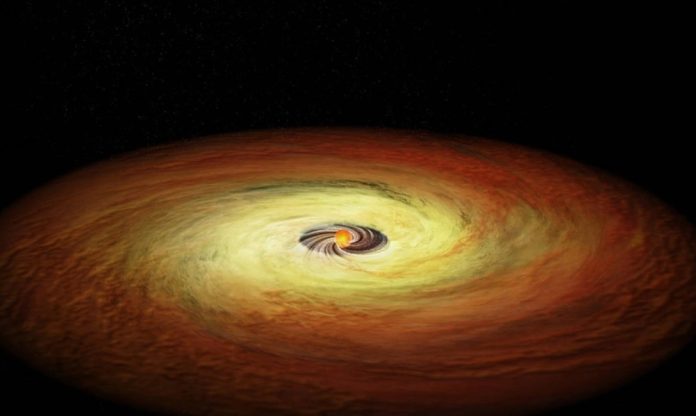

Astronomers have long believed that planet-forming disks—clouds of gas and dust around young stars—last only about 10 million years before disappearing.

But new observations using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) suggest that these disks can survive much longer in certain cases.

A research team from the University of Arizona has discovered a 30-million-year-old protoplanetary disk, three times older than expected.

The team, led by Feng Long, studied a star called J0446B, located 267 light-years away in the constellation Columba.

Unlike most stars, J0446B has retained its planet-forming disk for an unusually long time. This surprising find was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“Planet-forming disks give us a glimpse of what our solar system may have looked like when it was young,” said Long, a Sagan Fellow at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

Why do some disks last longer?

In most cases, the high-energy radiation from a young star blows away the gas and dust, causing the disk to disappear.

However, the study found that small stars—those with about one-tenth the mass of our sun or less—can retain their disks much longer. This means planets around such stars may have more time to form.

Despite its old age, the chemical makeup of J0446B’s disk remains unchanged, suggesting that its gas and dust have stayed stable for millions of years. This stability could be important for forming planets and possibly even conditions for life.

To confirm that J0446B’s disk is truly a protoplanetary disk and not a debris disk (which is made from second-generation material after asteroid collisions), researchers analyzed its gas content. They found hydrogen and neon, proving that primordial gas from the star’s birth is still present.

“This tells us that the disk hasn’t been replenished by asteroid collisions—it’s the original gas that has lasted much longer than expected,” said Chengyan Xie, a doctoral student and study co-author.

One of the most exciting aspects of this discovery is its connection to planetary habitability.

The TRAPPIST-1 system, located 40 light-years away, contains a low-mass star and seven Earth-sized planets, three of which are in the habitable zone.

Researchers believe that TRAPPIST-1’s unique planetary arrangement may have been shaped by a long-lived disk similar to the one found around J0446B.

“For planets to settle into the orbits we see in TRAPPIST-1, they likely had to move within a gas-rich disk for a long time,” explained Ilaria Pascucci, a co-author of the study.

While high-mass stars like the sun don’t seem to have long-lived disks, understanding how low-mass star systems evolve can fill gaps in our knowledge about planetary formation.

Since low-mass stars are far more common than sun-like stars, studying their disks could help astronomers learn how planets form across the universe.

“Finding these long-lived disks helps complete the photo album of the universe by giving us snapshots of planetary systems at different stages,” Long said.

Leave a Comment