former Energy Undersecretary and now “consumer advocate” recently attacked the Manila Electric Co. (Meralco) as being “unjust and unfair… charging households more than businesses,” referring to the lower rates for commercial and industrial customers compared to those of residential customers.

Petronilo Ilagan alleged that residential customers are subsidizing businesses. He used old numbers to make his argument, saying that residential customers pay “P1.8082 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for 1-200 kWh users, P2.1187 per kWh for 201-300 kWh, P2.4116 per kWh for 301-400 kWh, and P2.9220 per kWh for those consuming over 401 kWh.” These were June 2022 numbers.

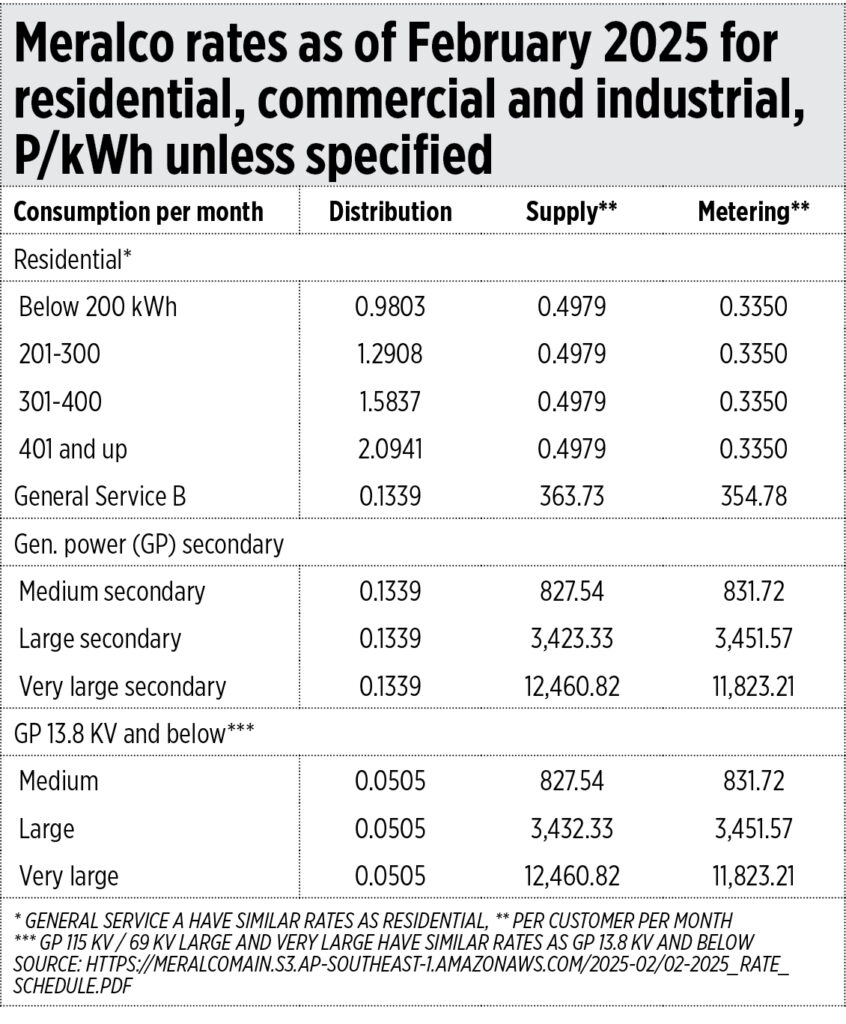

The most recent numbers are: P1.29/kWh for those consuming 201-300 kWh per month, and P2.09/kWh for those consuming over 401 kWh. In contrast, General service B and General Power (GP) Secondary customers pay only P0.134/kWh. The GP 13.8 KV pay even lower at 5 centavos/kWh. The supply charge and metering charge are up to P12,461 per large customer per month (see table).

Mr. Ilagan, who serves as president of the National Association of Electricity Consumers for Reforms, Inc. (Nasecore) is confused. Here are four reasons why.

1. The main concern of average residential or household customers like me is not “cheap at all costs” electricity but no blackouts. Electricity should be there when I need it, when I turn on the lights or the aircon. If electricity prices go up, then I can adjust by using an electric fan instead of an aircon, or turning off one or two of the many bulbs in the house. But when there is a blackout, my choices are horrible — either endure the darkness and inconvenience or light a candle. The latter is dangerous when a fire can accidentally happen, the price is damaged properties if not death to people.

2. The rates charged by private distribution utilities (DU) like Meralco are all regulated by the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) and not arbitrarily set by the DU. The current distribution charge rate has been there since 2003 and was not questioned for the last 22 years.

3. Setting up electric cables, meters, monitoring, and collection is more complicated and more costly with numerous small customers like households, compared with a single big hotel or mall or university.

4. The Electric Power Industry Reform Act of 2001 (EPIRA) Section 36 prohibits big customers from subsidizing residential customers, and businesses would be discouraged from coming into an area and creating more jobs if their cost of electricity gets even higher.

This attack on big DUs, the big generation companies, to force “cheap at all costs” electricity is only political noise and optics. The result would be “cheap but not available” electricity because the necessary cost and returns to entrepreneurship would not be met, so potential power businesses will not come into an area.

NGCP’S WACC

Recently the ERC set the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for the National Grid Corp. of the Philippines (NGCP) for the 4th regulatory period (RP, 2016-2020) at 10.71%. This is lower than the 15.07% under the 3rd RP (2011-2015, under NGCP), and 15.88% under the 2nd RP (2006-2010, when the grid was under TransCo’s management).

This low level of WACC — meaning a low transmission charge to be allowed — can be problematic in terms of infusing more capital for more big transmission projects as more power generation capacities are added, espe-cially for geographically scattered, small renewable energy projects like solar.

The NGCP shoulders the Concession Fee Payment, then the 3% franchise tax, which are now considered as not being part of the revenue building blocks, or not an expenditure item for recovery. Then there are nearly a doz-en recoveries as adjustments to the annual revenue requirement (ARR) — some dating back to the 2nd RP — which are now facing uncertainty of recovery.

The regulated sub-sectors of power transmission and distribution are problematic because each costing is subject to approval or disapproval by the ERC. As an economics writer and researcher, my approach is always to have a high but realistic growth target — like 7-8% annual GDP growth — and seeing what the inputs are — like power generation-transmission-distribution levels — that can support such high growth targets. Working backwards to identify bottlenecks, regulation should adjust, not prevail. Growth targets should prevail over regulation and bureaucratic requirements.

Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. is the president of Bienvenido S. Oplas, Jr. Research Consultancy Services, and Minimal Government Thinkers. He is an international fellow of the Tholos Foundation.

minimalgovernment@gmail.com

Leave a Comment