Primordial helium from the beginning of the solar system may be stuck inside Earth’s solid core, new research suggests. The findings could have implications for a long-standing debate about how quickly our planet formed.

This rare form of helium is called helium-3 because it has two protons and one neutron in its nucleus. Normal helium, which is 700,000 times more common than helium-3, is called helium-4 because it has two protons and two neutrons. Whereas helium-4 is a common product of the decay of radioactive elements, helium-3 comes almost entirely from the initial cloud of dust and gas that formed the solar system.

This primordial element was already known to exist inside Earth. Each year, about 4.4 pounds (2 kilograms) of helium-3 leaks out of mid-ocean ridges where the crust is pulling apart and out of volcanic hotspots that tap magma from the deep mantle. But exactly how it has remained inside the planet for billions of years is a persistent mystery.

Helium is a very light gas, and most volatile gases have long since escaped the mantle, having been blown away during the giant impact that formed the moon or churned to the surface by the inexorable movements of plate tectonics.

Scientists have theorized that perhaps this primordial helium is locked up in Earth’s core, where it would remain safe from major disturbances and leak out to the surface only very slowly. But the core is mostly iron, and helium and iron typically don’t mix.

Now, in a new study, researchers at the lab of Kei Hirose, a planetary scientist at the University of Tokyo, and their colleagues have found that at the temperatures and pressures expected in the core, the two elements actually do mix. In fact, solid iron at high temperature and pressure could contain up to 3.3% helium, the researchers reported Feb. 25 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

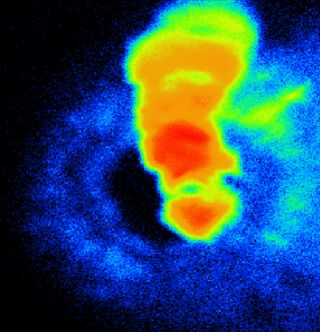

The researchers discovered this compatibility by heating iron and helium to between 1,340 and 4,940 degrees Fahrenheit (727 to 2,727 degrees Celsius, or 1,000 to 3,000 kelvins) while compressing the elements with a diamond-tipped anvil to between 50,000 and 550,000 times the pressure at Earth’s surface. Then, they depressurized the samples under cryogenic temperatures and measured their crystalline structures. This method likely prevented the escape of helium during the measurement phase, Hirose said in a statement.

The researchers used normal helium-4 in their experiments, but helium-3 would likely behave very similarly, said Peter Olson, a geophysicist at the University of New Mexico who was not involved in the study but studies Earth’s core. The findings confirm that helium could stay locked in Earth’s solid inner core for a long time, Olson told Live Science, but he cautioned that only 4% of the core is solid.

“This is significant, because it shows that helium is compatible with the solid phase of the core,” Olson said. “But because the core almost certainly formed in a liquid state, there is more work to be done to show that the same interpretation can be applied to the liquid part.”

Figuring out how helium-3 got incorporated into the core during Earth’s formation is very important for understanding when the planet formed, Olson said. Light gases like helium hung around in the gas-and-dust nebula that formed the solar system for only a few million years.

“It’s very much debated how long it took the Earth to form,” Olson said. “There is other evidence that has been interpreted to say the Earth formed very slowly, requiring 100 million years. You wouldn’t get much helium deep in the Earth if the Earth formed that slowly.”

In other words, if scientists can show that Earth’s core contains a lot of helium-3, it will strongly suggest that the planet formed quickly, settling a long-standing debate about the birth of the solar system.

What’s inside Earth quiz: Test your knowledge of our planet’s hidden layers

Leave a Comment