Scientists have spotted unique subtypes of fat cells in the human body, and by unraveling their functions, they found that the cells may play a role in obesity.

The research, published Jan. 24 in the journal Nature Genetics, could theoretically open up avenues for new therapies to mitigate downstream effects of obesity, such as inflammation or insulin resistance, the scientists said.

“Finding these [fat] subtypes is something very surprising,” study co-author Esti Yeger-Lotem,a professor of computational biology at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, told Live Science. “This opens up all kinds of potential future work.”

The findings suggest fat cells “are more diverse and complex than we previously thought,” Daniel Berry, a professor of nutritional sciences at Cornell University who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Fat cells have a ‘memory’ of obesity, study finds

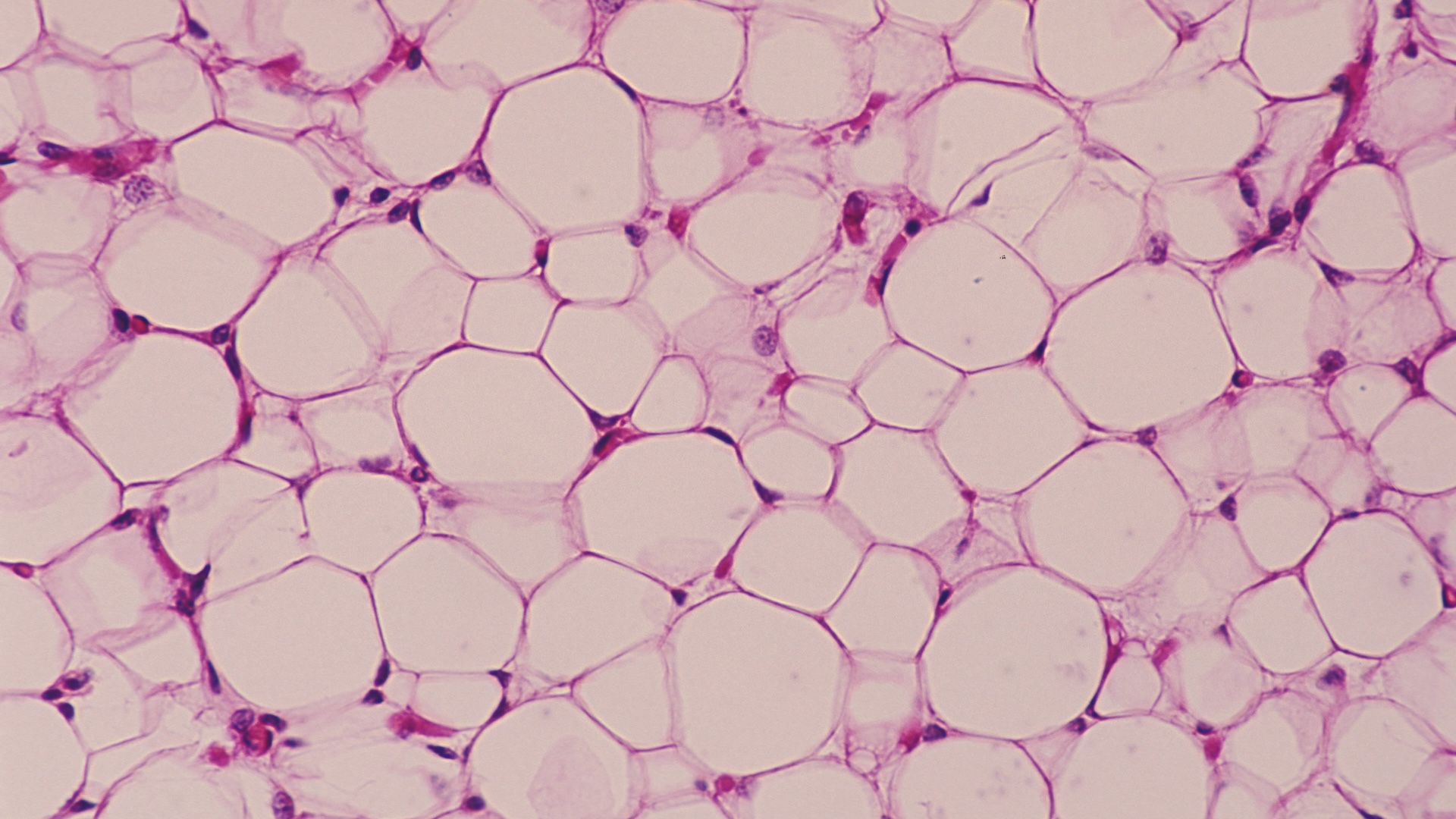

Over the past few decades, research has shown that fat tissue does a lot more than simply store excess energy in the body. For example, fat cells, also called adipocytes, and immune cells work in concert to communicate with the brain, muscles and liver. This, in turn, helps to regulate appetite, metabolism and body weight, and it’s also involved in related diseases.

“If something is wrong there,” within the fat tissue, “it affects other places in the body,” Yeger-Lotem said.

Not all fat is created equal

Scientists have also long known that carrying excess fat is linked with a risk of health conditions. However, one of the many aspects of obesity that have left scientists puzzled is that not all fat is created equal.

Visceral fat — fat cells that reside in the abdomen close to the internal organs — is linked to a greater risk of various health problems than fat under the skin, known as subcutaneous fat. For example, excess visceral fat comes with a heightened risk of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, insulin resistance and liver disease. Studies also suggest visceral fat is more “proinflammatory” than subcutaneous fat, which could potentially contribute to the ill health linked to obesity.

To better understand what might be happening inside fat tissues, Yeger-Lotem and her colleagues charted a “cell atlas” of adipocytes as part of the Human Cell Atlas, a global project that aims to map all the cells in the human body.

The researchers built this map using single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA seq), which measures which genes are active and to what degree by looking at RNA, a molecular cousin of DNA. RNA molecules act as blueprints for proteins, shuttling instructions from the DNA in the cell’s nucleus out to its protein-construction sites. By measuring RNA in the nuclei of cells extracted from fat tissue, the team gathered clues as to what each cell does inside the tissue.

Yeger-Lotem and colleagues examined samples of subcutaneous and visceral fat collected from 15 people during elective abdominal surgeries. Most adipocytes were fairly “classical” — meaning storing excess energy was their main purpose. But a small proportion of the fat cells were “non-classical,” as their RNA suggested they carried out functions not typically associated with fat cells.

Among these cells were “angiogenic adipocytes,” which carried proteins usually used to promote blood vessel formation; “immune-related adipocytes,” which make proteins related to immune cell functions; and “extracellular matrix adipocytes,” which are related to scaffold proteins that help support cells’ structures. These cell subtypes, found in both visceral and subcutaneous fat, were also confirmed under the microscope.

This “state-of-the-art application” of snRNA seq suggests these cells may play a role in “remodeling” fat tissues, Niklas Mejhert, a professor of endocrinology at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. Remodeling here refers to the way fat tissues change in response to weight fluctuations or metabolic changes. “Healthy” remodeling would help maintain metabolic balance, but if dysregulated, it could spur inflammation and other drivers of poor health in obesity, Mejhert said.

Related: In a 1st, scientists reversed type 1 diabetes by reprogramming a person’s own fat cells

The study also spotted differences in the newly described cell types depending on which tissue they were taken from. Unconventional adipocytes from visceral fat seemed more likely to communicate with the immune system than those found in skin fat, Yeger-Lotem said. This link to immune cells suggests the cell subtypes might play a role in triggering visceral fat’s proinflammatory nature, which could help explain why belly fat is worse for health.

The data also hinted that the fat-tissue donors with higher insulin resistance tended to have a higher concentration of these unconventional cells in visceral fat than did people with lower insulin resistance. However, Mejhert noted that the authors did not prove causation, so it’s not clear whether the cells might drive the insulin resistance in any way. It’s too early to know.

If these fat subtypes can be linked to human disease, understanding how they work could “help us fight inflammatory processes,” Yeger-Lotem said. That could potentially help doctors predict the risk of insulin resistance in people with obesity, assuming all the dots connect, she added.

Berry cautioned that the study used a relatively small sample size and that, at this stage, it only suggests rather than definitively demonstrates that the fat cells have these unusual functions. Still, “these insights highlight the importance of understanding fat depots’ unique behaviors to develop targeted treatments for obesity and related diseases,” he said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Leave a Comment