Researchers have discovered a link between a chronic gut infection caused by a common virus and the development of Alzheimer’s disease in some people.

Most people encounter cytomegalovirus (CMV) during childhood, and after the initial infection the virus remains in the body for life, usually dormant.

By the age of 80, 9 out of 10 people will have CMV’s telltale antibodies in their blood. A type of herpesvirus, the pathogen spreads via body fluids (such as breast milk, saliva, blood, and semen) but only when the virus is active.

In one unlucky group, the study showed, the virus may have found a biological loophole where it can remain active long enough to hitch a ride up the gut-brain axis ‘superhighway’, known more officially as the vagus nerve.

On arriving at the brain, the active virus has the potential to aggravate the immune system and contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s a concerning possibility, but it also means antiviral drugs might be able to prevent some people from developing Alzheimer’s, especially if researchers can develop blood tests to quickly detect active CMV infection in the gut.

Earlier this year, some members of the team from Arizona State University announced a link between a subtype of microglia associated with Alzheimer’s disease, named CD83(+) because of the cell’s genetic quirks, and raised levels of immunoglobulin G4 in the transverse colon, which hinted at some kind of infection.

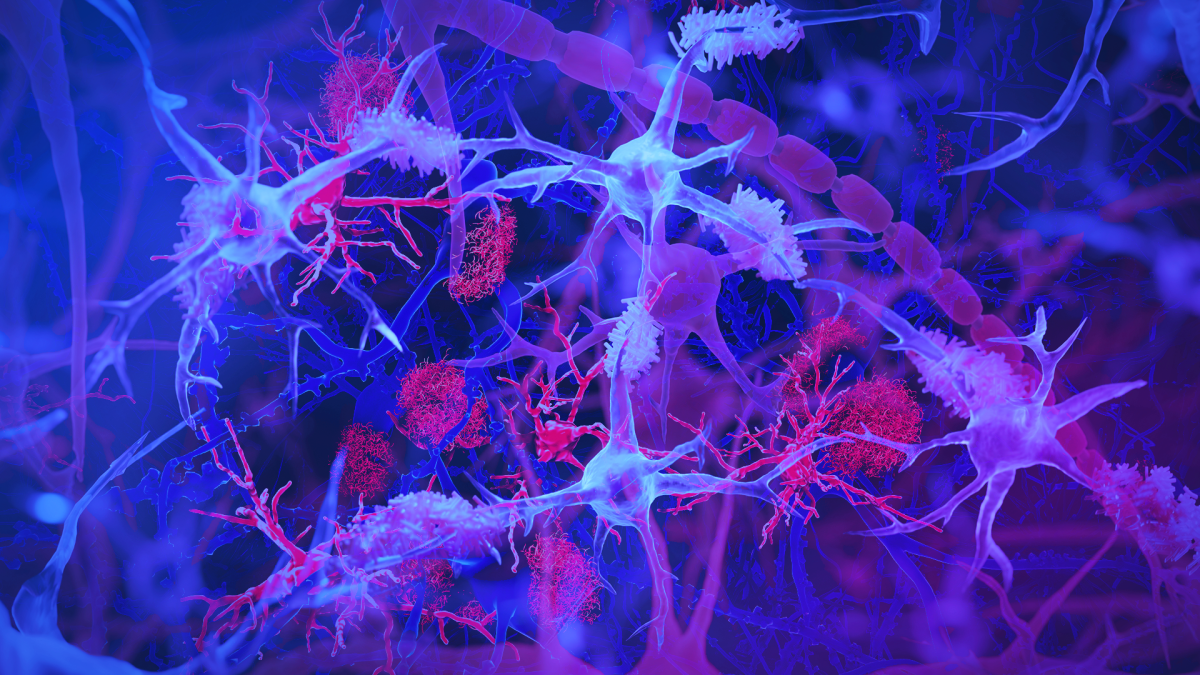

Microglia are the cells on cleanup duty throughout the central nervous system. They scavenge for plaques, debris, and surplus or broken neurons and synapses, chomping down on them where possible and setting off the alarms when infection or damage is out of control.

They’re here to help, but if the microglia are constantly being set off, unleashing their inflammatory weapons without pause, it can lead to neuronal damage that’s associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

“We think we found a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s that may affect 25 percent to 45 percent of people with this disease,” biomedical scientist and lead author Ben Readhead from Arizona State University says.

“This subtype of Alzheimer’s includes the hallmark amyloid plaques and tau tangles – microscopic brain abnormalities used for diagnosis – and features a distinct biological profile of virus, antibodies, and immune cells in the brain.”

The researchers had access to a range of donated organ tissues, including the colon, vagus nerve, brain, and spinal fluid, from 101 body donors, 66 of whom had Alzheimer’s disease. This helped them study how the body’s systems interact with Alzheimer’s disease, which is often considered through a purely neurological lens.

They traced the presence of CMV antibodies from donors’ intestines, to their spinal fluid, up to their brains, and even discovered the virus itself lurking within the donors’ vagus nerves.

The same patterns showed up when they repeated the study in a separate, independent cohort.

Human brain cell models provided further evidence of the virus’s involvement, by increasing amyloid and phosphorylated tau protein production and contributing to neuron degeneration and death.

Importantly, these links were found only in a very small subset of individuals with chronic intestinal CMV infection. Given that almost everyone comes into contact with CMV, simply being exposed to the virus is not always cause for concern.

Readhead and team are working to develop a blood test that will detect intestinal CMV infection so it can be treated with antivirals, and perhaps prevent patients from developing this type of Alzheimer’s.

The research was published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Leave a Comment