More than 60 years after Uganda gained its independence from the United Kingdom, the legacy of racial segregation still sullies the air in the poorest parts of the country’s capital city, Kampala. The areas where colonizers forced African populations to live are still the most economically vulnerable neighborhoods in the city of more than 1.8 million people. They also face the worst air quality, new research has shown.

In the parts of the city inhabited by Africans during the period of segregation, levels of fine particulates known as PM2.5 are high enough to reduce life expectancy more than tobacco use or HIV infection, said the study’s lead author, air quality scientist Dorothy Lsoto of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“When you look at the air quality in these different places, it’s striking,” Lsoto said. She and her collaborators will present their findings on 12 December at AGU’s Annual Meeting 2024 in Washington, D.C.

Decades of Air Quality Inequities

Colonial-era policies and infrastructure have left economic imprints across many cities in Africa, economists have shown. Public health specialists have long suspected that part of this legacy extended to the air in these neighborhoods, but they lacked the data to explore this question.

“Does this history still play a role in how air quality looks?”

“Does this history still play a role in how air quality looks?” asked Lsoto, a Ugandan citizen and researcher from Kampala who went to Madison for her doctoral training.

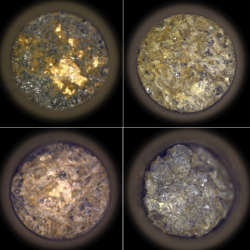

For years, the high cost of traditional monitoring equipment prevented people in Kampala from accurately assessing the quality of their air. Newly designed sensors, however, cost a tenth as much as traditional sensors and can be repaired using more widely available parts. The AirQo project at Makerere University in Kampala deployed more than 50 monitors with this updated equipment across the city.

To explore the connection between air quality data and neighborhood status, Lsoto and her colleagues compiled 2014 census data about everything from income level to firewood use into a social vulnerability index (SVI). They mapped the SVI across Kampala to identify the economic status of each community.

They then compared that map to the newly measured PM2.5 levels and immediately found a prominent overlap: People in areas with higher vulnerability, including those near landfills and industrial parks, live with far higher PM2.5 levels than other city residents.

A Lasting Colonial Legacy

When Lsoto and her colleagues looked for the cause of such disparities, they didn’t have to look far. A historical settlement map from 1951 showed clear correlations between the current PM2.5 levels and SVI and the boundaries of communities that were colonial-era African settlements. Even after comparing these communities to those that were colonial-era European settlements with similar roadway density, green space, and fuel use today, air pollution remained elevated in African settlements.

“The way the city was designed is going to keep on reinforcing the disparities of air pollution.”

“The way the city was designed is going to keep on reinforcing the disparities of air pollution,” Lsoto said. She noted that Europeans lived on the tops of hills, pushing Africans into crowded urban slums in the valleys next to polluting industries. Pollutants such as PM2.5 tend to settle in valleys. Low air-mixing rates and cool air sinking into the valleys at night trap the particles.

After independence was gained in 1962, segregation ordinances were lifted. Wealthier Ugandans moved into the former European settlements, but poorer Ugandans remained in the urban slums.

“I think this is one of the first few papers investigating the historical causes of the exposure inequalities [in Africa],” said Yuzhou Wang, an air quality engineer and postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. The high cost of monitoring air quality in low- and middle-income countries makes it difficult to detect local trends and change policies, Wang said.

In Uganda, public health specialists are trying to address profound differences in air quality with the National Environment (Air Quality Standards) Regulations, 2024, launched in May, mandating that cities create policies that reduce air pollution. Study coauthor Alex Ndyabakira works with city agencies, ministries, and community leaders to address air pollution in his role as the supervisor of medical services at the Kampala Capital City Authority.

Building trust is vital, Ndyabakira said. “We want [air quality monitors] to be owned by that community.”

—Rita Aksenfeld, Science Writer

Leave a Comment