A stressful life can leave marks on our genetic code, some of which can even passed on to our children. A study now reveals how the biological impact of trauma on a mother persists long after the violent acts themselves have passed.

The international team of researchers demonstrate the physical mechanisms behind intergenerational trauma in humans, explaining why people with a family history of adversity are more prone to mental health conditions like anxiety and depression, despite not having experienced the adverse events themselves.

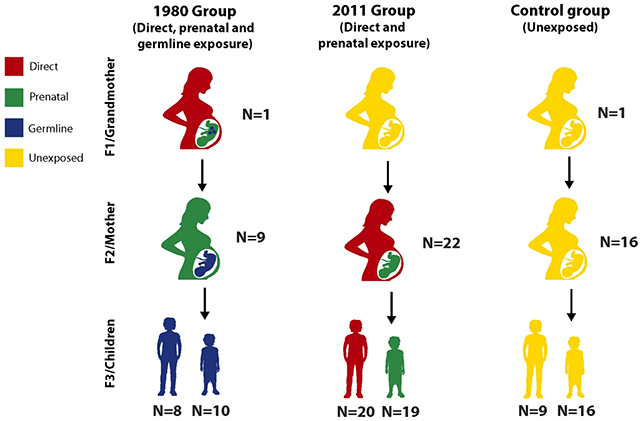

The researchers analyzed DNA collected from 48 Syrian families across three generations. These families included grandmothers or mothers who while pregnant had fled the 1982 siege and massacre in Hama or the 2011 armed uprising – both part of the ongoing Syrian civil war.

Working closely with these families, who now live in Jordan, the researchers were able to collect cheek swabs from 131 individuals, which were then analyzed for shifts in epigenetic signatures. These aren’t changes in the DNA sequence itself, but in chemical alerations that affect how sequences function.

“The families want their story told,” says University of Florida anthropologist Connie Mulligan. “They want their experiences heard.”

Using families who left Syria prior to 1980 as controls, the team found modifications in 14 genome areas related to violence in individuals whose grandmothers were involved in the 1982 Hama attack.

What’s more, eight of these modifications persisted through to the grandchildren, who had not experienced the violence directly. The results also featured indications of accelerated epigenetic aging, potentially increasing the risk of age-related disease. In addition, another 21 genome areas showed signs of alterations caused directly by violence in the Syrian civil war.

The changes observed by the researchers were consistent across victims of violence and their descendants, suggesting that it was the stress of conflict that had changed the chemical messaging associated with these genes.

These kinds of lasting, multi-generational gene changes in response to stress have previously been observed in animals, but until now there’s been little research into how this might also work in people.

What isn’t clear from the study is how these modifications might impact each individual’s health. But the researchers say they came away with a lasting impression of the perseverance of these families.

“In the midst of all this violence we can still celebrate their extraordinary resilience,” says Mulligan. “They are living fulfilling, productive lives, having kids, carrying on traditions.”

“They have persevered. That resilience and perseverance is quite possibly a uniquely human trait.”

Of course, there are many more destructive consequences of violence for the victims and their children – including significant harms to mental health and physical health covered by previous studies, which aren’t quickly forgotten.

According to the researchers, these findings are likely to apply across many forms of violence, including domestic violence, sexual violence, and gun violence. These acts have lasting effects far beyond those involved.

“The idea that trauma and violence can have repercussions into future generations should help people be more empathetic, help policymakers pay more attention to the problem of violence,” says Mulligan.

“It could even help explain some of the seemingly unbreakable intergenerational cycles of abuse and poverty and trauma that we see around the world, including in the US.”

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.

Leave a Comment